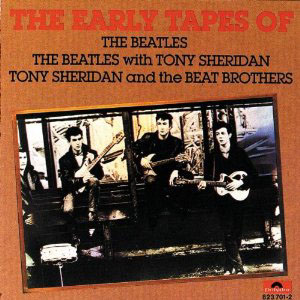

The Early Beatles: Great Freedom, Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers

The Early Beatles: Great Freedom, Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers The Early Beatles: Great Freedom, Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers

The Early Beatles: Great Freedom, Tony Sheridan and the Beat BrothersBy Kevin Robbie

Thursday Review Contributing Writer

In 1960, the Beatles traveled to Hamburg, Germany for a two-month engagement at the Indra Club. The group’s members were very excited as this work represented their first somewhat legitimate employment a band. Their part-time manager at the time, Allen Williams, had signed a contract with Bruno Koschmider, a German businessman who owned the Indra and other clubs. British bands were the rage in Hamburg and Koschmider had been anxious to secure another group from Britain.

However, Koschmider was also a gangster whose rackets included prostitution and drugs. His clubs were the among the seediest in Hamburg’s Reeperbahn district. The Reeperbahn was intersected by two main streets—the Grosse Freiheit (Great Freedom) and the Herbertstrasse. The area was packed with dive bars, clip joints, all-night partiers and loud music. There were also enough garish brothels and prowling girls to convince any young man he was in a sexual candy store. The Beatles, who had never been outside of Britain, were not immune to the temptations.

One of the most popular British performers in Hamburg was Tony Sheridan, who died in February at the age of 74. Born in Norwich in May, 1940, Sheridan was an accomplished musician, but the raucous German crowds—usually fueled with copious amounts of alcohol—were more impressed with Sheridan’s energy and stamina. He was also known for playing his music at an ear-busting volume. Nothing was considered over-the-top on the Reeperbahn. Sheridan’s loud, wild performances matched the raw intensity, bright neon and blaring sounds of the Reeperbahn. Over time, Sheridan developed a devoted cult following in Hamburg.

The Beatles were certainly aware of Sheridan’s prowess on the guitar and his popularity in Hamburg (his favorite guitar at the time was a Martin Dreadnought). After their own shows the Beatles would walk over to the Top Ten Club to take in Sheridan’s act. The Top Ten was owned by Peter Eckhorn, a rival of Bruno Koschmider. The Beatles approached Koschmider about paying them more money and providing them with better living accommodations. Since their arrival in Hamburg they had been living in two small, dank cubicles behind the screen of the Bambi Kino, a seedy theater owned by Koschmider. He rejected their requests out of hand.

However, the Beatles weren’t just sitting in the audience at Sheridan’s shows. Eventually, he invited them to participate as his backing band, an offer they eagerly accepted. Their contract with Koschmider forbade employment in any venues not owned by him. They were naïve enough to believe they could get away with it. Thus he turned down their pleas for increased pay and better rooms. On the other hand, the Beatles weren’t paid when they performed with Sheridan. They did it for the love of it.

Koshmider made the next move. Infuriated at the Beatles refusal to back down on their legitimate requests for better working conditions, he began using his connections to the police. Hamburg had a curfew requiring minors to be off the streets by 10:00 p.m. George Harrison was only seventeen and a minor under the law. The Beatles’ work schedule required him to be out long after the curfew deadline. He also had no work permit. The cops ordered George to be out of the country in 24 hours. Having no other choice, George complied. Within a few weeks, the rest of the group were back in Liverpool, exhausted and disillusioned.

After several weeks of moping, they gathered themselves together and began playing gigs in and around Liverpool again, performing in venues such as the Casbah, the Cavern and Litherland Town Hall. Audiences familiar with the Beatles realized they weren’t the same group as the one that left for Hamburg four months earlier. The music was tighter and they were much more confident onstage.

In March, 1961, the Beatles returned to Hamburg and contracted to play at Eckhorn’s Top Ten club for two months. But they had moved up in the world and were listed on playbills as co-stars with Tony Sheridan. The group also had a change in personnel as Stuart Sutcliffe, their erstwhile bassist, left the group in order to pursue his art studies in Hamburg and marry his girlfriend, Astrid Kirchherr. Paul McCartney then became the group’s bass player.

The Beatles pairing with Tony Sheridan proved to be a bonanza for Eckhorn. The Top Ten was packed with people and their shows were described as energy-charged extravaganzas. Sheridan enjoyed working with the Beatles as their vocal harmonies—and intensity—impressed him and complemented his act. He also respected their improving musicianship. But he was still far ahead of the Beatles in that regard and adding his guitar to their sets pushed their music into overdrive.

Before the Beatles left Germany to return to Liverpool, they were seen at the Top Ten by Bert Kaempfert, a German bandleader who was moving into talent representation. Kaempfert was intrigued by the Beatles but he was more impressed with Tony Sheridan. He signed Sheridan to a recording contract with the Beatles as his backing band. They were, of course, overjoyed by the news. A number of songs were recorded and “My Bonnie” was selected for release. On the label, the Beatles were listed as The Beat Brothers, the collective name used for all of Tony Sheridan’s backing bands in the early 1960s. They were paid 300 deutschmark, about $75.00 at the time. Eventually, the record sold 100,000 copies in Germany.

According to Beatle legend, Brian Epstein first heard of the group when a boy named Raymond Jones walked into Epstein’s NEMS record store in Liverpool and asked for a copy of “My Bonnie” featuring a local group called the Beatles. However, the story is almost certainly not true. The Beatles themselves frequented NEMS to listen to records. The stores’ salesgirls also knew the group. NEMS also had posters on the walls announcing Beatles’ appearances. And Mersey Beat, a local paper covering the Liverpool music scene, put news of the Beatles record contract on its front page. Mersey Beat was selling very well at NEMS and the paper’s founder Bill Harry, had been asked a question by Epstein–“What about this group the Beatles?” After making further inquiries regarding the group, Epstein decided to see them performing. He did so at the Cavern Club on November 9, 1961, and, of course, the rest is history.

It’s now been over fifty years since the Beatles raucous days in Hamburg and their collaboration with Tony Sheridan. By serving as an unofficial mentor for the group, Sheridan influenced the Beatles early sound and helped them hone their musicianship and stage presence. Against the backdrop of the “Great Freedom” and the Reeperbahn, the Beatles began to gel as a band.