Right now, in Washington, D.C., members of the U.S. House of Representatives are quarrelling feverishly over the fate of our nation's spending, Democrats and Republicans making some of the same arguments that were made 31 years ago this very month, each side accusing the other of causing the stalemate, each side issuing threats, each side promising to hold their breath until they turn blue.

Back in the spring of 1981, President Ronald Reagan, still slowly recovering from a collapsed lung and other injuries sustained by an assassination attempt, spent several hours of each workday on one singular task: winning over support for something called Gramm-Latta, officially known as the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981. Gramm-Latta, which was named for Representatives Phil Gramm (R-Texas) and Delbert Latta (R-Ohio), was Reagan's first step toward fulfilling-or attempting to fulfill-the campaign promise of less government spending and lower taxes. The bill reduced or limited government expenditures in nearly every area except defense spending. Thanks to a GOP landslide in November of 1980, Republicans controlled the Senate in 1981, but it was Democrats who still controlled the House. Nevertheless, Gramm-Latta had plenty of allies among Democratic moderates and fiscal conservatives who saw eye-to-eye with Reagan when it came to government spending, and in late June of 1981 the bill passed.

Later that year the Senate would pass Kemp-Roth, the tax-cut bill named for Senators Jack Kemp (R-New York)-a dedicated supply-sider and a persuasive early political advocate for lower taxes-and William Roth (R-Delaware), and the legislation most closely associated with Reagan's original economic thesis. But that summer, the back-and-forth was all about Gramm-Latta, and after the original version was presented, liberal Democrats in committee began to systematically chip away at the bill's stringent belt-tightening. Before long, billions of dollars were squeezed back into a bill designed to reduce spending. A famous pissing match ensued between House Speaker Tip O'Neill and President Reagan (they were friends when they were away from their political day jobs) in which each accused the other of being out of touch with working men and women. O'Neill and Reagan even argued over which one of the two had grown up closer to the railroad tracks in their hardscrabble youth. But despite intense pressure by Democratic leadership on the moderates and conservatives their own party, the bill was not watered down, and Gramm-Latta (known in Capitol lingo as Gramm Latta II) passed narrowly.

Coupled with Kemp-Roth, these two pieces of landmark legislation marked the first major setback in decades for the reliably spendaholic behavior of nearly every Congress since the start of the New Deal, a template of governmental action which says that federal dollars and federal management are the most effective weapons to be deployed in any given social, cultural or infrastructure environment--from schools to clinics to lunches, from bridges to light bulbs to solar panels.

But, as we know now, these two historically important bills--surely muscular and far-sighted--nevertheless lacked the important third leg of the tripod: a plan to curb or control deficit spending. Our debt grew during the Reagan years, and it increased faster than it had during the 1970s. Much needed and long overdue Defense spending accounted for a large part of that deficit growth, a fact that enabled many conservatives at the time (myself included) to turn a blind eye to the hard cost of challenging the Soviet Union at a critical period in the Cold War. Besides, Reagan had it right on that point: the United States and its allies could not possibly win the Cold War simply by sustaining the will to not lose the Cold War. The long term cost would be too great, so better to confront the threat. The U.S. and its allies had flexible, dynamic economies; Moscow and its proxies in Prague, Pyongyang and Belgrade did not. We accepted the grim, unseemly process of deficits, vastly upgraded our military, and in turn bankrupted the Soviets and brought about the speedy collapse of Marxist-Leninism.

Liberals argued at the time that we cruelly sacrificed social services and safety nets--letting the poor and the homeless and school lunches suffer. Conservatives argued that no such sacrifice would have occurred since the true cost of these services was administrative, not on the front lines. And besides, by the end of 1981 and early 1982 Congress, unable to control its deeply-placed pathology for spending, had found ample opportunities to get around Reagan's spending cuts. The result was that both defense spending and non-defense costs rose, side-by-side. Meanwhile, over at the Federal Reserve, then-chairman Paul Volcker was doing everything within his power to slay the beast of inflation by sharply limiting credit and micro-managing the money supply.

Predictably, this combination triggered a recession, the third or fourth major recession since the early 1970s. (In short order the country staggered out of the '81/'82 recession, which was mild by today's standards, and soon entered into a period of economic stability and growth which would remain mostly unbroken for the next 20 years).

Still, some things never change, and many of the same arguments are being made today, 31 years after Gramm-Latta II. The hyperbole surrounding the threats and counter-threats leaves the American people disgusted with Congress and disgruntled with Presidents who seem powerless to shape a long-term solution. Raising the debt ceiling, lowering it, locking it where it stands--the arguments inevitably circle back into partisan quibbling: Democrats accuse Republicans of wanting to deliberately deepen the divide between rich and poor; Republicans accuse Democrats of being conspicuous spenders and credit card junkies.

Even the decades-old arguments about defense spending versus social services spending are back in play, with Democrats seeking to reduce defense costs and asking for a solid agreement of the withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014, and Republicans pushing for higher military spending and weapons upgrades which exceed even what The Pentagon has asked for in its discussions with President Obama. Mitt Romney, campaigning as the presumptive GOP nominee, has proposed a major upgrade to the U.S. Navy--a sound enough idea considering the age and condition of the Navy's ships, submarines and weapons systems--but a plan for which there is no known price tag, and even less clarity on the subject of how it will be paid for with American tax dollars.

Furthermore, Congress has a famous inability to resist pork, a continuing resistance to the elimination of earmarks and the bundling of expensive pet projects, and virtually nothing standing in their way when they choose to green light still more debt. And in an election year no member of Congress will summon the inner courage to do what's right... yet, we expect Congress to behave rationally and in our best interest. This is like expecting a gambling addict to not merely ignore an unlimited line of credit being offered at a casino, but also to ignore the free room, the free meals, the free airline tickets and the free limo ride to get there.

The question can be put forth simply: how much debt do we want to pass along to our children and grandchildren? The answer is none, but that clearly understates the complexities we face: heavy war debts from Iran and Afghanistan; the intractable and metastasizing conundrums of Social Security; a Congress unwilling to consider closing tax loopholes and a President unwilling to take action on entitlement reform; and an economy still struggling to scrabble its way from severe recession.

So, accompanied by the usual harsh language and the typical threats by Representatives, we face some of the same challenges we faced 31 years ago this month, only now the price tag for inaction can be multiplied a hundredfold. Members of Congress wonder why they have such low standing among Americans, and why many people liken the goings-on under the Capitol dome to monkeys at an all-you-can-eat salad bar.

Congress's most predictable feature is its willingness to defer politically tough choices to the next Congress, and, in the larger sense, to the next generation. In that respect there is reliability.

But, votes still count, and Americans still have the power to change the behavior of Washington.

Subscript:

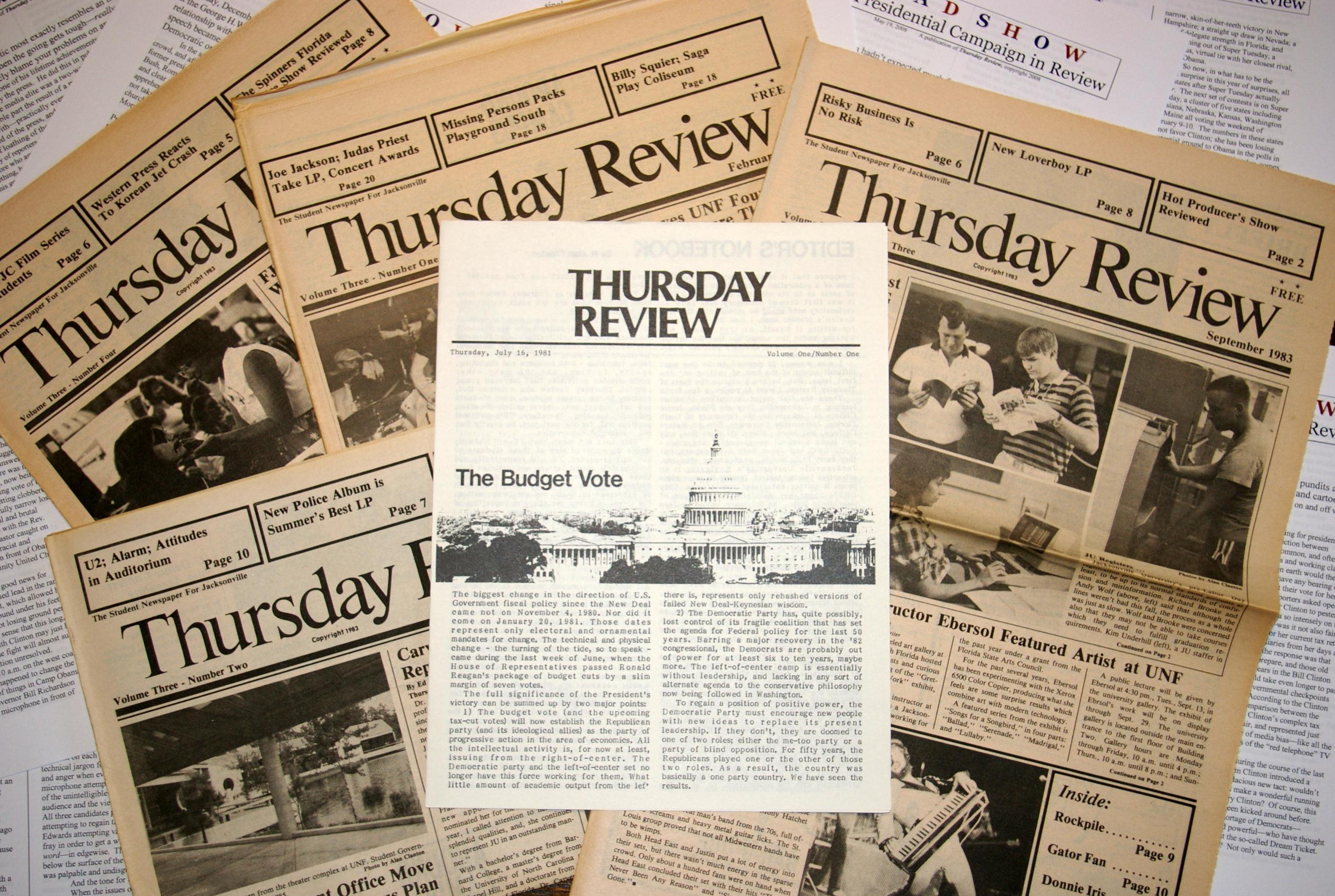

During that same time period a group of mostly conservative Republican students and young people--ranging in age from 17 to 31, and many of them former active volunteers who had logged countless hours working on behalf of Reagan's 1980 campaign--were in the process of putting together the first edition of an off-campus newspaper in Jacksonville, Florida, a publication meant to be an alternative to the standard student journalism available at the time in northeast Florida. The first issue was little more than an eight page newsletter, but Thursday Review would soon morph into a tabloid-sized, web-press newsprint monthly (our original goal had been to have a new edition every other Thursday).

It lasted about four years before we suspended operations. Though it was filled with paid advertising, it never made a profit, and instead hovered near the break-even point most months. The largest issue, February 1983, was 28 pages, filled with a wide variety of content ranging from student news, music and concert reviews, movie reviews, national and local politics, book reviews and cartoons. Its ample advertising space was 100% sold and totaled over $2700. After all expenses were paid--typesetting, film and developing, screen art and halftones, commissions to the ad salesmen, a handful of small fees to some of the writers, and finally printing--we had $39.50 left in our account at Flagship Bank.

Back then there were no virtually no personal computers with the flexibility and power which we take for granted now. All articles had to be typed (remember typewriters?), triple-spaced, and hand-delivered to a printer or ad agency or type shop, where a friendly professional typesetter would re-type every inch of copy. (Some months the fee for typesetting exceeded the cost of printing.) A day or two later someone would call and say the galleys were ready, and we would take those long, coated strips of paper--waxed on the back--and, using scissors and art knives, slice them up and place them carefully on our paste-up boards. Photos, freshly converted into what were called half-tones, were also arranged by hand using the same method, along with the ads and almost all of the other art. Borders, page numbers, headings, decorative dingbats and flourishes were applied painstakingly to the boards, and then everything was carefully examined. This is what one would lovingly call Old School. It was a pain in the ass.

As owner-editor-publisher, and as someone who had taken three years away from college to work full-time on Thursday Review, it had become a backbreaker, and one which paid me almost nothing beyond covering a few of my own expenses. So, early the next year, when the monthly net continued to range from $30 to $90, we shut it down.

The re-invented Thursday Review emerged first as an email only newsletter using my AOL account back in the early aught years, when I wrote a series of articles about politics and movies which were mass emailed to a few dozen friends. Around that time I started a compilation of reviews called 99 Movies Worth Comment, which we hope to add soon to the existing Thursday Review site. Later, in mid-2007, I began Road Show, a weekly review of the presidential campaign. It was a simple newsletter which was emailed to friends and interested parties, and, in a few cases, mailed. Road Show became the key ingredient in the newly reinvented Thursday Review you see now, but we are steadily adding new features and sections, as well as inviting more writers to participate.