By R. Alan Clanton

Thursday Review Editor

October 22, 2012: When we think of the great rivalries of contemporary times, our first instincts often take us to sports. There was Muhammad Ali versus Joe Frazier, perhaps the greatest boxing rivalry in what was surely one of the golden ages of pugilism. Then were those mid 1970s match-ups between two of pro football’s most powerful teams, the unforgiving defensive curtain of the Pittsburgh Steelers and the dazzling, high pressure offense of the Dallas Cowboys. And there was Bjorn Borg versus John McEnroe, a rivalry of talent unparalleled in single combat sports and a stylistically asymmetrical pairing which produced the most famous tennis match in history.

That sports metaphors roll all too easily into political analysis is a more-or-less permanent condition of American journalism—and indeed writers as far back as the FDR versus Wendell Willkie contest of 1940 have been deploying gridiron images and top-of-the-ninth-inning wordplay so frequently that we rarely stop to think about what, if anything, these breezy references mean. The sports comparisons often wander into cliché. Even politicians enjoy the analogies. Richard Nixon often spoke of politics as “an arena,” and neither Gerald Ford nor Ronald Reagan could ever quite leave behind the football analogies—Ford because he had played on the gridiron in college, Reagan from his early days as a sportscaster.

The intense combativeness of the last few election cycles—especially those since 2000—has exaggerated this tendency to paint elections in the images of the Super Bowl, the World Series, or the Stanley Cup. Giants versus Broncos, 1987. The Thrilla’ in Manilla. For lazy political writers and analysts looking for a quick verbal analogy, it’s just too easy.

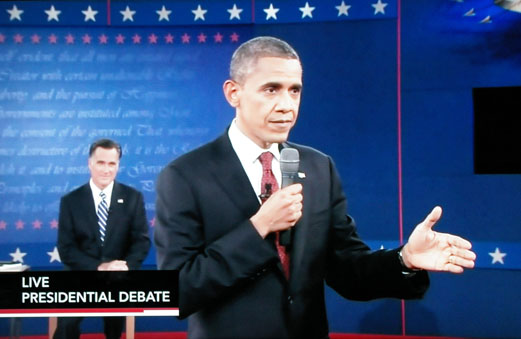

Still, it was hard not to walk away from last week’s debate between President Obama and his challenger Mitt Romney without a sense that this political contest has become a sport—as bloody as boxing, as bruising as football, and as tactically demanding as tennis—with every word and every gesture part of a live feed of activity so intense that even the best handlers and spin managers cannot control the torrent of talk. In the current atmosphere of partisan entrenchment and often shrill, unchecked language, the brutality becomes an unfortunate adjunct to the arena.

When the September edition of The Atlantic magazine featured a cover story analogizing the presidential debates as a boxing bout—complete with photos of Romney and Obama lookalikes sparring violently in the ring—little did writer James Fallows and The Atlantic’s editors realize just how intense the actual combat would become by this week’s debate, the second of three scheduled match-ups between the President and Romney. Eight years ago a similar Atlantic cover story prepared us the for the certainty of asymmetrical combat between then-President George W. Bush and his challenger, Senator John Kerry, but without the sports allusions. In 2004 we were, after all, waist deep in two major wars.

But this year the stakes are higher and the focus has shifted. Obama’s inability to translate his skills as conciliator and post-partisan orator into actual bipartisan traction has left his presidency largely at sharp odds with any definition of success. Conversely, Mitt Romney’s wants to boil the message down to a simple, straightforward replay of 1980—offering up the question of are you better off but generally leaving out any specifics. That the first debate between these two men went badly for the president and produced a winning outcome for Romney should have come as no surprise. Obama suddenly seemed as small and vulnerable as Jimmy Carter, and Romney became—overnight—as presidential as Ronald Reagan.

But there were more debates, and more time for the narrative to evolve. Reagan’s knockout blow to Carter came with only a week remaining before Election Day. Romney’s shellacking of Obama came early, with over a month of space between the first contest and that One Day Sale at the polling places. This meant of course that there was plenty of time for a “correction” on the part of Obama and the White House.

So, the President put on the beef and the bulk, and Romney dug in his heels—far more dangerous to be cast as the sudden front-runner than it is to stalk from slightly behind. Though it contained substance, the intervening match-up between Joe Biden and Paul Ryan generated more jokes and punch-lines than it produced actual political traction for either camp. Undecided voters were unmoved, and the rest saw the VP debate as a draw, the result of partisans simply affirming their predispositions.

So last week’s rematch between Obama and Romney was not so much presidential debate as single warrior combat. Is boxing the best analogy? Perhaps. But over the next few days some of my own friends—Republicans and Democrats, conservatives and liberals—offered independently of one another that the forum in Hempstead, New York was in fact more like professional wrestling. All that was missing was a cheap folding metal chair with which to slam the referee.

Sports references aside, the question becomes one of substance—not style: Were Americans in fact served in any significant way by the latest debate?

The answer, unfortunately (but also perhaps predictably), is an unqualified no. Little was settled, and even less was revealed or illuminated. After twelve days of being thrashed for his poor performance in the first debate, the President overcompensated and came out swinging with wild haymakers and kicks to the groin, and in the process offered almost nothing in the way of specifics. Romney, equally charged and primed to retain his advantage, also over-reached, morphing into a more subdued version of the very playground bully Joe Biden we had witnessed the week before. Neither candidate really addressed the issues in any substantive way. Most of their energies were expended on the tedious business of alpha male showmanship and almost childish one-upmanship—frequent interruptions, salient moves into one another’s personal space, contentious belaboring of each disagreement and pointless semantic challenges.

Even the arguments with moderator Candy Crowley put strains on the already difficult task of giving the town hall participants a chance to ask questions, the result being that very few of the average voters present had a chance to participate.

When valid questions were raised, the two candidates spent the lion’s share of floor time avoiding a substantive answer and instead launching into fruitless harangues of their opponent’s words or deeds, real or conflated. A question about women in the workforce and the advancement of women in management roles led to Romney’s biggest misstep, and a remark about how as governor he had a “binder full of women” as evidence of his commitment to promoting qualified females. Romney was also seen as having fumbled the ball when the issue of Libya and the recent violence in Benghazi was raised, insisting that the President had not spoken of terrorism the day after the attacks, when in fact he had—obliquely, to be sure.

The President seemed to continually offer an alternate-universe view—that of a country with more new jobs, more energy independence, and greater economic opportunity—in direct disregard for reality. Further, Obama’s chief strategy seemed to consist exclusively of refuting or disputing every word that Romney spoke, even the most obvious things and even those items which did not—in fact—require contention. This too wasted valuable time and provided a running distraction bordering on the comedic.

Indeed, the last two debate cycles—the VP debate from two weeks ago and now this most recent match-up—have been fodder for a thousand jokes on a thousand blogs, as well as an endless stream of gags on scores of television shows. Saturday Night Live, with an already established tradition for skewering such political events, has enjoyed the easiest form of comedy writing that one can employ: copying real life. This past Saturday’s episode opened—in what is known in live TV jargon as a cold open—with a spot-on, hilarious send-up of the New York debate, complete with verbal taunts, trash talk and semantic silliness. The irony of the SNL sketch was how little the writers had to alter reality to make their satirical debate into an absurdist send up of our political status quo.

The obvious downside to this is voter frustration and apathy. When candidates representing both major parties make the conscious choice to so overtly avoid answering the issues of the day—especially in a forum designed to make it as easy as possible to field such concerns—voters tend to tune out.

Tonight’s debate in Boca Raton gives both campaigns an opportunity—one last time—to speak honestly and directly to voter concerns. Let’s hope the forum is used for that purpose.