By R. Alan Clanton

Thursday Review Editor

November 10, 2012: Let’s cut to the chase: The Republican Party has problems. Once a political party whose electoral base virtually guaranteed a path to the White House—the Grand Old Party now sits in a precarious and awkward spot, with Presidential victory seemingly out of its reach, and a deepening shortfall in the U.S. Senate.

For now, demographics and Congressional districting handiwork in many states still give the GOP an edge in the House of Representatives, but that’s the only glimmer of good news for Republicans who woke up Wednesday morning to President Barack Obama’s re-election. Even the consolation prize, Mitt Romney’s once-handsome election night lead in the popular vote, had begun slipping away as midnight approached on the east coast, and by the wee hours the sluggish returns from the most stubbornly slow counties put the President in a lead which grew still larger by sunrise. By early morning on Wednesday, November 7, the House built by Teddy Roosevelt, Robert Taft, Tom Dewey, Dwight Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan was a shambles.

The blame game had started even before the sun came up. Mike Blumberg was at fault. Chris Christie was at fault. Colin Powell was to blame. Karl Rove was to blame. Hurricane Sandy was the cause.

Obama had been the Man to Beat for Republicans—a large, moving target on the swelling high seas, harpooned and lanced continuously for four long years—and after a billion dollars were deployed in the form of advertising, you’d think they would have at least seriously wounded their whale. Nothing of the sort happened, and despite a close battle in the popular vote, Obama emerged with what Democrats will no doubt describe fairly as an electoral mandate, especially in the context of a slight power shift in the Senate.

The failure of mega money to redirect energy from the popular President brought a tactical reality check:

A far more difficult reality for the GOP brass and the strategic pathologists among Romney’s team is the loss of the swing states. Ohio, as we had been told a thousand times by a thousand reporters, was the key: no Republican has won the White House without the Buckeye State. In the end, even the results from the most reliable of GOP strongholds north of the Mason-Dixon Line, Hamilton County, failed to put Mitt Romney over the top.

But Romney had other options, and other pathways, complex though they were. These were the Plans B through G, if you will—a mathematically dizzying series of if-this-happens, then-this-will-happen scenarios, all of which seemed uncomfortably optimistic. The problem was that by close to midnight all of those fallback plans had failed as well. None of the true swing states—Colorado, Nevada, Iowa, New Hampshire or Virginia—went Romney’s way, despite an early surge for the former Governor in Virginia which created some excitement for several hours. Nor did Romney benefit in any of the long-shot states: Wisconsin, Michigan, and the Hail Mary pass, Pennsylvania. Romney’s wins in Indiana and North Carolina proved to be his only real vindication of the night, for he was able to redirect those states from their 2008 blue status to the red column.

And Florida, where balloting is always a source of national entertainment and the brunt of a thousand jokes, remained stubbornly deadlocked, with voters reportedly still lined up at some polling places at 2:00 a.m. eastern time. Reports early Saturday indicate that the Florida Secretary of State will validate the results as an Obama win, since the President maintains a narrow lead. Hundreds of military votes remain uncounted, but those will not be enough to tip the scales toward Romney. Still, there’s little reason to expect the Sunshine State to bestow an after-the-fact door prize for Romney, and its windfall of 29 electoral votes would do little to blunt Obama’s smashing victory. Florida—host state for the Republican convention—never should have been that close for Romney anyway. Broadly hardwired by local Republicans, it was a must-win, and its failure to deliver a decisive tilt toward the GOP is a testament to the severity of the party’s national sickness.

To be sure, the Republican Party of Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bob Dole and Newt Gingrich, isn’t dead—far from it. But there is work to be done, a lot of work.

The GOP that awoke Wednesday morning finds itself in the same uncomfortable spot that the Democratic Party occupied several times during the 1980s—out of power, and seemingly out of touch with the constituencies that should be its natural, greater base.

For a variety of reasons the Republican Party has lost its way during the last decade. This cannot be blamed entirely on George W. Bush or Dick Cheney, the traditional whipping boys when talk turns nasty and the analysts and commentators want to assign blame. In fact, one could easily argue that the fault resides in the most contemporaneous of factors—which is to say in the events of the last 24 months.

First, there was the Tea Party, a movement seen from the outside—and self-identified from within—as a more-or-less spontaneous uprising by average people against everything that Barack Obama allegedly stood for, which is to say a wide range of real or imagined transgressions against liberty, freedom and prosperity. Deliberately decentralized and avowedly independent, the Tea Party nevertheless quickly found itself intertwined into the structure of a Republican Party all-too-willing to accept this insurrectionist movement into its ranks. When the GOP made substantial gains in the House and Senate races of 2010, the Tea Party movement and the Republican regulars formed an uneasy—and some would argue, unworkable—alliance. In the end, the Tea Party did very little to shape national politics in the traditional sense, nor did it sway Democrats or liberals or halt the momentum of progressive causes. What it did accomplish was a partial but significant internal restructuring of the GOP, an unnecessary, and as it turns out, unwise step.

The Tea Party—as well as the quasi-aligned movements of super-rich patrons of anti-government, anti-Obama causes—lured the GOP along a dangerous path. At first, some Republicans welcomed this infusion of energy and viral street frustration, as well as the cash. The movement initially seemed a rightist mirror of similar activity by the largely self-organized Occupy forces of the Left, a spontaneous collective outpouring of rage against the system—millions of Americans shouting at their windows I’m mad as hell as if guided by Paddy Chayefsky’s Howard Beale himself. But, largely unmanaged by political pros and therefore prone to unfiltered political incorrectness, the Tea quickly soured, morphing instead into unproductive anger. Largely white, largely middle class or upper middle class, the movement came too easily to be described by the liberal media as a “backlash,” and little else—a ragtag of Caucasian agitation focused on “taking back our country,” which often meant the overt language of anti-immigration, anti-social services, anti-government, anti-tax, anti-Obama. A landmark Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United Versus the Federal Election Commission enabled the flowering of a thousand sources of deep-pocket spending, nearly all of it generating the illusion of an even wider movement of support based on rage and grassroots angst.

To be sure, there was legitimate outrage to be harnessed—the staggering expansion of food stamp eligibility and its related programs, for one—and a ramping up of social dependency that rivaled Lyndon Johnson’s most ambitious, far-reaching dreams. Social collectivism was back in vogue, and opponents of this leftward tilt had a real grievance that such a national slide toward dependency is, at its best, overwhelmingly expensive—especially to those who work—and at its worst, anti-Democratic. But the value of the message seemed lost amidst the shouting and mismanaged language. Mainstream Republicans did little to redirect this cacophony into more constructive, media-friendly terms, and the protest movement would soon be labeled by analysts and reporters as a rabble of quasi-racist haters. Nevertheless, Tea-aligned candidates sprang up in numerous congressional contests, in some cases even challenging entrenched traditional Republicans. Again, this did little to realign popular or independent thinking, but instead began the process of pivoting the GOP toward more strident positions in issues ranging from immigration to taxes to negotiation with Democrats. The center was already being lost, and many independent voters took several steps backward—away from the GOP.

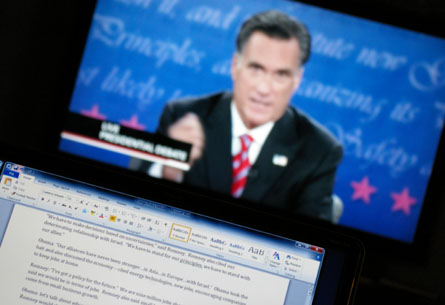

Then, beginning in the late spring of 2011, the Tea Party and its wide array of compatriots found their way into the early Presidential sweepstakes. No longer satisfied to act as a mechanism for change in Congress, and tapping successfully into the manifest frustrations of an economy at its lowest ebb, these grassroots groups—backed in many cases by wealthy donors—enabled the spectacular rise of the GOP insurrection, a summoning of a series of anti-Romney challengers bent on proving themselves capable of higher levels of fidelity to movement conservatism. Predictably perhaps, Romney became their stand-in for President Obama, and through the long series of televised debates—many of the contests watched by remarkably large audiences—the anti-Romney’s assaulted the presumed front-runner with withering cross-fire. Fox News and CNN in particular placed high value on these match-ups, promoting them as if the events were a form of full body contact sports. Ratings soared as Romney became the human piñata, even as the Republican candidates agreed ostensibly to have as their common goal the defeat of Barack Obama in 2012.

The irony was profound to some, bitter to others. Three years earlier conservative purists and talk radio commentators (Glenn Beck, Ann Coulter, Rush Limbaugh, among many others) had engaged in a high stakes but short-lived rebellion when it became apparent that Senator John McCain, the conciliator and closet moderate, would ascend to the nomination past Mitt Romney—for at that time it was Romney who was regarded as the true heir to the legacy of Ronald Reagan. The nastiness subsided only after McCain selected Alaska’s Sarah Palin as his running-mate. But, a few years later, in the late spring and mid-summer of 2011, Romney was the one being pilloried as a shadowy, crypto-liberal, and a creature of the GOP establishment and the Washington insider’s club.

The debates gave rise to a kind of Gong Show procession of challengers, each briefly embraced and elevated by the seething forces of anti-Washington and the Anybody-But-Romney movement. Each candidate in turn had their moment of star power and glory—Michelle Bachmann, Rick Perry, Herman Cain—and each in turn faced implosion, sometimes with spectacular results. With Fox News chief Roger Ailes frequently fanning the flames, Texas governor Rick Perry and former Massachusetts governor Romney sparred on occasion with what seemed an antipathy teetering at the edge of physical violence. Romney, a seasoned debater from his challenges to Ted Kennedy in the 1990s and his epic debate battles through 2007 and 2008, remained upright and stoic throughout, but when forced off of his script by the shrill attacks he made mistakes, as when he challenged Perry to a ten thousand dollar bet at a time when most Americans counted themselves lucky to have their next paycheck. The debates began to burnish the notion that there were few, if any, adults in the room among those on the stage—or, in some cases, the audience. Fox News even encouraged the jeering, the tittering and the booing. The GOP debates became a surreal form of entertainment—part professional wrestling, part Survivor, part Fear Factor.

There was also a sense among the Republican faithful, especially those of an Old School mindset, that theirs was a party was already veering off course. The debates, maddeningly accompanied by high ratings, reinforced a notion that there were no wise, genteel elders in the room to mediate—no grandfatherly figures or great aunts able to offer words both soothing and resolute; there was no Ronald Reagan, no William Buckley, no Jack Kemp, no Milton Friedman. Until late spring of 2012 even George H.W. Bush remained silent, seemingly biding his time until Romney would finally emerge as the de facto nominee. Revered figures who once sat or worked in the Oval Office, those who had shaped opinion and divined meaning, those who had once shepherded the intellectual and grassroots movements of conservatism—are largely, if not entirely, vanished. Many Republicans watched the interminable series of debates and felt unsatisfied with their options, and uneasy about their fate.

Still, excitement would occasionally swell, then, ebb back into a disappointing reality.

Political novice Herman Cain arrived on the scene as a real businessman, a self-made man who had worked the front counters at Burger King and Godfather’s Pizza, building real companies, generating real profits, and hiring real workers. Cain was another anti-Romney and an instant favorite of those opposing the former Bain Capital money wonk by then being portrayed by his fellow Republicans as a creature of a greedy Wall Street and pernicious outsourcing. Cain, like Bachmann, Perry and Pennsylvania’s Rick Santorum, introduced a dynamic which drove the conversation further to the right, leaving Romney isolated as the dangerous moderate who had once conspired with Ted Kennedy on health care legislation.

After the demise or self-destruction of Bachmann, Perry and Cain—and the predictable marginalization of Jon Huntsman—the field narrowed to the Final Four. Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum emerged as the stars of the insurrection, waging a tenacious challenge to the notion of Romney as the inevitable nominee. Ron Paul attacked from the libertarian quarter, frequently keeping the conversation honest in terms of the U.S. Constitution, but offering little in the way of traction for a GOP destined to face Barack Obama in November. Gingrich and Santorum as movement conservative and social conservative respectively, fought with dazzling tenacity to derail the Romney juggernaut. The path Santorum followed was a trail already blazed in part by Mike Huckabee four years earlier, and, it could be argued, by social conservatives and evangelical Republicans since the days of Pat Robertson’s candidacy in 1988.

Santorum, especially, deprived Romney of vast tracts of Middle America, and forced Romney into a defensive, fixed-fortification strategy through many states. In numerous primaries the outcome was similar: Santorum would sweep an enormous swath of rural areas, small and medium towns, and occasional exurban counties, leaving Romney with the numerical consolation prize of the cities and affluent Republican suburbs. In one week Santorum won three states, sweeping Colorado, Missouri and Minnesota, and placing Romney’s self-generated image as the de facto leader in serious jeopardy. It was clear that Republicans were deeply divided, with Gingrich pulling half of the insurrection toward him, and Santorum the other half toward his cause. Some Romney strategists saw in this a divided opposition, but even analysts like CNN’s Jon Avalon pointed out that the true metric was how effectively Romney’s opponents were at simply denying Romney the magic number of 1144 delegates.

In a party generally more disciplined and front-loaded—traditionally able to produce a de facto leader no later than late January—this internal feud summoned chaos and even panic. It was the Democrats who were supposed to attack each other with chainsaws and machetes, not Republicans.

Add to the spectacle the media fascination. The longevity of the process was by now generating spectacular ratings for MSNBC, Fox News and CNN, not to mention driving up viewership on a hundred politically-focused websites and blogs (and in fairness we should disclose that such was the case here at Thursday Review). But through all of this scrutiny there was the necessary adjunct: independent voters and non-aligned voters, and especially some younger voters, were watching. Though it would be unfair to characterize either Gingrich or Santorum as strident, their occasional unfiltered faux pas—on minimum wages, on women in combat, on birth control, on Palestinians, on Obama’s belief that every young person deserves a college education—drove the conversation repeatedly into the ditch and gave reporters an endless source of material for the stories of a GOP out-of-touch with average Americans. Santorum and Gingrich were effective communicators most of the time, but in those unguarded one percent moments, their words were used to bludgeon a Republican Party already straining to find a voice among independent voters.

When Romney sensed movement on his right flank, he jerked reflexively.

Even before the Iowa Caucuses and the New Hampshire Primary, and even before the much-ballyhooed South Carolina primary—Romney was forced into increasingly awkward defenses of his tenure as governor as Massachusetts. Though he could have easily managed this conversation to his distinct advantage—painting his self-portrait as that of a conservative willing to work sensibly and pragmatically within the boundaries of what is arguably the most liberal state in the nation—Romney chose instead an ineffectual path which included obfuscation and denial. On issues ranging from abortion to gay marriage rights, from taxation to health care (the governor was the author of Romneycare, a forerunner of Obamacare) Romney was forced to engage in elaborate dance steps in order to remain the central front-runner, in many cases disavowing his previous positions in an attempt to protect his right flank. Romney seemed at every campaign stop and in every debate to pander.

Still, the narrative kept shifting uncomfortably toward the boundaries of stridency.

During the much-watched and heavily promoted debates—30 total, spanning a wide range of geography from Iowa to Nevada to South Carolina to multiple venues in Florida—much of the Republican sparring was over degrees of conservatism. Rick Perry was pummeled over a program in Texas allowing for educational access for children of illegal immigrants. Rick Santorum was harangued for his fondness for earmarks. Newt Gingrich was berated for his relationship with failed mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Michelle Bachmann took incoming fire for her statements about STDs and vaccinations for children. And Romney was hammered for—everything. Newt Gingrich, long self-identified as a charter member of the Reagan Revolution, was belittled for the one scant reference Reagan made in his own diaries to the man who would become Speaker of the House.

Through all of this Romney became a contortionist, bending to suit the demands of the moment and operating—as many successful business leaders do—at the behest of the changing dynamics of the market. But Romney’s flexibility, what would normally be seen as a smart form of adaptability in business, came across as insincerity to many who watched this process unfold. Romney came too easily to be seen as a candidate with little, if any, true political or social convictions.

Even after the demise of Santorum and Gingrich, many conservatives were decidedly uneasy of Romney—and many remained deeply skeptical—as he sailed comfortably toward nomination, for the perception was strong that was a flip-flopper and serial panderer, a plastic cyborg candidate willing to do or say anything to win. In fact, Romney did not succeed in finally securing unconditional support from some on the Right until his early August selection of Paul Ryan as running mate. Ryan was a Reaganesque fiscal conservative and a reliable favorite among the true believers.

Worse for the former Governor were the class distinctions: across a wide battery of polling before and immediately after the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary, Romney fared well with Republicans whose earnings exceeded $200,000; he scored low among GOP voters who earned less than $100,000 per household, and even lower among those who earned less than $50,000. Later polling directed at Democrats and independents clearly showed a further widening of these numbers. This social disparity was profound, and the gap seemed only to grow into February and March. In a recession still viewed largely as a product of an amoral Wall Street and the greedy whiz kids of financial firms, Romney was being systematically portrayed as a creature of big money. Even well into April, when he was numerically secure in his capture of the nomination, Romney was—as he predicted all along—attacked even more unrelievedly by liberals, Democrats and the Obama campaign for his wealth and the class distinctions, using ordnance already field tested by his Republican opponents. Even his fundraising efforts began to come under assault from Democrats and an increasingly hostile media—exclusive $25,000 a plate private dinner parties in the Hamptons to raise campaign cash—even though Obama had participated in similar high dollar and celebrity fundraising events in Beverly Hills and Los Angeles.

The worst finally came when a video emerged on the website for Mother Jones—a leftist journal—depicting Romney at a fundraiser in Boca Raton. In the video, captured on a hidden camera, an unguarded Romney suggests that 47% of Americans have little reason to ever consider voting Republican or even listening to the former governor’s message, for their political allegiances are linked inextricably to their dependency on government social services. Though some in the GOP might believe something akin to this formulation, no serious candidate should ever utter such words. The fallout was mighty and almost ceaseless, sparking an immediate response from Democrats who made Romney’s words part of a widely aired TV commercial. Clips of the video went viral, and were shared via the internet millions of time within only days. Romney’s words were used as a blunt weapon by Democrats even at the state levels all across the country.

Oddly, even some liberals noted that the printed transcript of Romney’s words seemed—on the whole—less than menacing and uncaring, and more like the kind of words spouted a thousand times every day on a thousand blogs and radio talk shows. In fact, in most print accounts, the text seemed almost anti-climactic—certainly not much of a smoking gun. But as video content—in commercials and in television news bits—the clip makes one squirm. Surely somewhere Marshall McLuhan was laughing from his grave. A largely compliant media deemed the video to be central to the conversation for the remainder of the election news cycle, odd considering that the White House and the Obama team in Chicago had already made the deliberate decision to go both low-road and harshly negative in their “comparison” ads about Mitt Romney—depicting the governor as a creature a Wall Street greed and a single-minded devotion to multi-billionaires. Romney remained a member of the one percent.

Still, there was plenty for the Romney team and the Republicans to be optimistic about, for by early to mid-summer most Americans still viewed the economy as the central issue, and many of Obama’s 2008 supporters were among those younger Americans whose job outlook was the bleakest. There was a sense that the passion for the President had largely evaporated, and that the only task for the GOP would be to woo those in the middle. The message would be a simple one, and Romney—with fiscal conservative Paul Ryan as his running mate—would merely have to pose to uncertain voters the now-famous Reagan question: are you better off now than you were four years ago?

Indeed, in Tampa, this became the central theme—as it should have been. But the convention scripters and planners and speechwriters made little effort to reach out beyond the limited comfort zone. Eighteen months of conversation had lifted and relocated the boundaries. There was hardly any mention of support of the military or the troops—either those still in the field fighting in Asia—or those at home. There was virtually no mention of veterans of the most recent wars, nor of past wars. The word Afghanistan was mentioned only once in three days of continuous speeches. Iraq was mentioned only twice. Despite a procession of eloquent and attractive Latinos to the podium—Marco Rubio, Susana Martinez, Luis Fortuno, to name but three—there were scant few faces in the Tampa Bay Times Forum representative of voters of the wider Americas.

As for African-Americans, the outreach was negligible. In the fall of 1979, as a young activist and writer, I attended a state Republican convention in Orlando, Florida—called Presidency One—an event meant in part to serve as an early beauty contest for the GOP presidential candidates for 1980. Speakers included Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bob Dole, John Connally, Harold Stassen, Phillip Crane and others. There were some 50 or 60 African-Americans attending that meeting, out of roughly 600 delegates present—at a statewide convention. By direct comparison I counted fewer than 40 black delegates at this year’s national convention out of the thousands of delegates on the floor of the arena, and only about the same number in the visitor and guest sections.

These disparities felt profound, even in a longer contemporary context. There was a time when conscientious conservatives like Jack Kemp and Lamar Alexander, traditional patricians like George H.W. Bush, social conservatives like Pat Robertson, and more recent pragmatists like Jeb Bush, took great pride in their openly-stated mission of reaching out to voters whose skin is brown or black, especially through the resonate message of economic improvement. During the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush there were nearly twice as many African-Americans who described themselves as Republican as there are now. For Latinos, the numbers have literally reversed since the 1980s, giving Democrats at two-to-one edge in a demographic group once heavily inclined toward the GOP.

However, other than a few minor misfires, Clint Eastwood’s strange bit of minimalist improve, for example, the Republicans had a good convention. The major speeches were effective and in many cases soaring, certainly for GOP standards. The highlights included Condi Rice, Paul Ryan, Tim Pawlenty, Jeb Bush, and a remarkably effective nominating speech by Marco Rubio—the rising star of the GOP’s Latino outreach.

And there was New Jersey governor Chris Christie’s forceful call for Republicans to roll up their sleeves and get to work. In hindsight, this speech seems strangely prescient, for the text infers the grave potential for missed opportunity by Republicans, not to mention the full import of the possibility of events larger than the muggy, sometimes smarmy arena of politics—a tidal change, as it were—for now Republicans truly have their work cut out for them.

(This article is Part One of a series of essays on the outcome of the 2012 elections. Part Two will follow in a few days.)