Leonard Nimoy, Rest in Peace

| published February 28, 2015 |

By R. Alan Clanton

Thursday Review editor

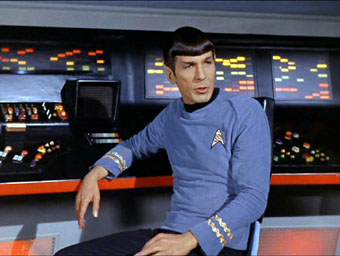

Although in his many decades as an actor he appeared in more than 65 features films, in some 150 different television shows, and in at least 150 productions for the stage and theater, he was still indelibly marked as the character of his most famous portrayal—that of the hyper-logical but endearing Spock in the sci-fi TV series Star Trek.

Leonard Nimoy, whose appearances in three short seasons of Star Trek made him an icon for science fiction fans worldwide for generations, died this week in Los Angeles from end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nimoy was 83 years old.

Nimoy was versatile as an actor—whether on stage in performances of The King and I or in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, or as the narrator-moderator of the long-running series In Search Of…, a highly popular show dedicated to examining the great unexplained mysteries of our world, or as painter Vincent van Gogh in a one-man show crafted to delve into the inner thoughts and torments of the famous painter.

But Nimoy was also versatile in the manner of a Renaissance Man: he wrote for the screen and stage, directed and produced films and TV, painted on canvas, wrote multiple books (including two biographies and several books of poetry), and was so good at photography that it became very nearly his second career.

And though his early career had been peppered with only modest success as a frequent extra, cameo actor, or character performer, especially in the early days of television, his fame was sealed for the ages after those few seasons of the innovative and cerebral Star Trek show gained traction in reruns.

Star Trek itself had an odd arc to its success. Created by Gene Roddenberry, it started as a quirky pilot episode with a somewhat different cast in 1964. That episode was titled “The Cage,” and starred Jeffrey Hunter as Captain Christopher Pike, John Hoyt as Dr. Boyce, and Susan Oliver as Vina. Nimoy landed the part of Spock. When the finished show was presented to the NBC top brass, they frowned upon it—famously calling the thoughtful and intellectual finished product “too cerebral.”

Still, the suits at NBC saw something in it, and they knew from their research that TV shows about space exploration would fit nicely in the age of Gemini and Apollo missions, and what was perceived at the time as the nearly unlimited frontier that our solar system and galaxy had to offer. They sent Roddenberry back to the drawing board to rework the concept, and—in a gesture rarely extended to anyone who delivers a loser the first time around—told Roddenberry to produce a “second pilot,” an bit of an oxymoron in Hollywood. That unsual second opportunity, most TV historians have said, was the result of a desire by a few execs at NBC to find a space travel angle that would catch on with viewers.

Nimoy would benefit mightily from this fluke do-over moment: he would be one of only two cast members from the first pilot to make it into the second pilot (Majel Barrett was the other). Nimoy would keep his character of Spock intact—albeit with a few minor adjustments—though Barrett would essentially start over in a new role.

Roddenberry went to work hammering away at something that would please NBC, carefully reworking the script called “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” After great struggle, using a new cast, and employing scrupulous editing, the second pilot seemed to please NBC, which greenlighted the show for a fall 1966 rollout.

Shooting for the real-deal debut began soon afterwards, and within a few weeks the scripts introduced the more familiar faces and characters, including William Shatner as Captain James T. Kirk, Deforest Kelly as Doctor Leonard McCoy, James Doohan as chief engineer Scott (aka, Scotty), and George Takei as Lt. Sulu. Also introduced was Nichelle Nichols as communications specialist Lt. Uhura, a bold move by Star Trek’s production company Desilu and NBC: never before had an African-American woman been placed in a top-tier role in a U.S. TV series. And then there was Nimoy, back again after two pilots in his role as Spock.

The first regular show debuted on the night of Thursday, September 8, 1966. Its ratings thereafter were a mixed bag of modest-to-low numbers, and the show got uneven reviews in the entertainment press: some reviewers liked it, some panned it, still others expressed ambivalence toward a show with such potential for moral complexity mixed with futuristic space travel.

It ran from September 1966 to June 3, 1969, eventually canceled by the executives at NBC even before the show reached the end of its third season. The show’s ratings were so lukewarm by the middle of the second season that several of the principal actors sensed it would soon end, and started working with their agents to find other work for the following year. Shatner famously told friends that he would be unemployed as of the last day of shooting for Season Two. Remarkably, the show survived a Season Two death and was renewed for at least one more year.

But ratings were still wobbly, and the TV show widely regarded as the most brainy and far-reaching ever attempted was given its final goodbye at the end of Season Three.

For those who slept through the 1960s, or for those who disdain anything that touches sci-fi or space exploration, Star Trek’s premise was simple enough: in the 23rd Century, earthlings and their closely-kindred humanlike spirits within a territorial and governing area known as the United Federation of Planets, send spaceships whizzing about the known universe in search of distant life, new civilizations, and differing cultures. Each show began with a brief paean to this concept, voiced by Shatner as Kirk, followed by opening credits juxtaposed upon images of the spacecraft Enterprise soaring at blurring speeds from one planet to the next, from one star to another.

The beauty of such a broad template was that it delivered what could be described as near-infinite flexibility to the writers—few limitations were placed on imagination, save for what could not be easily of effectively achieved using the special effects of the day, or by using imaginative make-up and costuming. A typical episode might take the ship and crew into a presumably hostile section of the galaxy, where beings of unimaginable strength or mental powers would test the resolve and skill of the crew. Television being what it was in those days, Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Scotty and company would have one hour of screen time in which to outwit or outsmart their superior alien adversaries. This would normally involve a mix of cagey trickery and impassioned eloquence by Kirk, and patient, methodical logic by Spock, sometimes with Dr. McCoy—acting as foil to Spock (for whom he feigned a sort of mild, endearing hatred)—intervening as the most irrationally “human” of the high ranking crew members.

This tripod of interaction—Kirk versus Spock versus McCoy (we understood Kirk to be extremely close friends with both Spock and McCoy)—became the essential engine of an unspoken under-theme, with Spock often acting as the most compassionate member of the team despite—or perhaps because of—his devotion to logic and reason. McCoy’s frequent flare-ups of emotion and impatience, too, reflected both humanity, and the yin-yang of the human condition. Those interactions between Spock (who was, after all, half human, half Vulcan) and McCoy were often used for comic effect, but just as often revealed the nature of humanity’s truest enemy—human beings.

Nimoy grew into the role of Spock so effectively and so completely that it remains difficult to imagine the series without his persona. Years after the series had been cancelled, the big budget motion picture franchise that ensued with great box office success included far more script attention to Spock than the series had ever offered—an indication that the character had become as beloved as any among the cast.

The growth of Star Trek’s following after the show was cancelled remains one of television’s most enduring post-mortem success stories. And its later success has its roots in Season Two. Despite declining ratings and a sense that the show was operating on borrowed time, including continuing mixed press reviews—a counter-phenomena was developing. NBC took note that of all the fan mail it received for all of it 1960s programming, Star Trek was—by late 1967—drawing remarkable stacks of mail, second only to The Monkees. During Season One Star Trek attracted 29,500 letters; Season Two saw that number nearly double.

When rumor leaked out that Star Trek was perched precariously on the NBC chopping block, Roddenberry and others convened a letter writing campaign which they hope would spark a thousand or more appeals. Within a month however, NBC received some 116,000 letter. Thousands more poured in from students at Caltech and MIT, and in January 1968 roughly 200 science students from Caltech marched on NBC studios in Burbank, California (the first time a mass rally had been organized for a TV show). Science students also led rallies in New York and other cities, and a separate letter-writing campaign began when graduate students, professors and academics at scores of universities began campaigning to keep the show alive.

As the letters arrived in larger stacks, NBC took the extraordinary step of announcing on air immediately after the March 1, 1968 episode (it was the voice of Don Pardo) that the show had been renewed for another season. NBC execs were hopeful that with the announcement the letter writing would stop. But it did not. Word leaked out that Star Trek’s budget had been cut deeply, which many in the business understood as NBC’s way of severing life support to the show.

Finally, and only after much internal wrangling about its March on air promise to keep the show alive, NBC pulled the plug after production was completed for episode 79, principal shooting of which ended in January 1969.

Star Trek’s cancellation amidst such a vigorous grassroots campaign proved immediately beneficial to the show’s enduring success. Syndicators almost immediately wanted the show. Independent station owner Kaiser Broadcasting quickly bid for the rights to replay the show in the afternoons and evenings opposite the local and national news of CBS, NBC and ABC—a time slot regarded as prime real estate if the local station had a Big Three affiliation, but widely viewed as trash time for any other station. After all, what would one watch in those days except Walter Cronkite or Chet Huntley? That one hour to 90 minutes for an independent station was a ghetto into which little of value could be placed, even reruns.

But Star Trek’s legion of loyal followers in some big city markets—New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago—meant that the show’s rebroadcast had value even when pitted against local and national news. And for the first time in TV history, a show in syndication occasionally beat out the big three networks in some cities and on some nights between six and seven. If wasn’t a fluke, either, as ratings for Star Trek reruns kept steadily climbing. Its fan base continued to climb as more and more younger viewers, many of them under the age of 25, and many in their teens, started to migrate toward the show in massive numbers. By late 1970 the show was picked up fully by Paramount, and by mid-1971 it was already one of the most successful reruns in history.

Then, that quirky, brainy sci-fi show that had been cancelled by NBC in 1969 made history again when, in 1972—largely because of the foundations created by those massive letter writing campaigns—sparked the organization of a fan club unlike anything television had ever seen. Trekkies, who sometimes preferred the term Trekkers, held their first major convention in New York City in late 1972. Instead of the 750 its organizers had originally expected to be in attendance, the event drew more than 3000. Within a month, similar events were being organized in Miami, Los Angeles, Baltimore, Chicago and San Francisco.

Meanwhile, Paramount saw interest in the show swell among all those local TV stations looking for high quality rebroadcast material for their scheduled, especially the late afternoon and early evening blocks. Incredibly, Star Trek was rapidly becoming the most popular syndicated show in history by the end of 1972 when it was already being aired on more than 100 television stations in the United States and dozens more in Canada and England. By 1986, Star Trek had become the most popular syndicated show of all time, surpassing the rerun power of I Love Lucy, Bonanza, Gilligan’s Island, and Andy Griffith combined.

But for Nimoy, the close cultural connection to the show developed into a love/hate relationship, at least in the heady days of the 1970s. His first biography, I Am Not Spock, was meant—most readers felt—as a repudiation of the character which by then had subsumed him as an actor and strangely thrust him into sci-fi iconography. Like his colleague Shatner, he found it difficult—even at times impossible—to shake the legacy of a show which grew in stature year after year. But Nimoy would eventually come to respect and even love the enduring power of his Star Trek persona. His second biography, I Am Spock, completes the circle of his relationship with the iconic character which so defined his career as an actor.

And in fact it made him a multimillionaire in the even headier days when Hollywood took over the helm of the Star Trek franchise (1979 through the 1990s) and guided it through innumerable motion pictures, television incarnations, TV spinoffs, movies based on the spinoffs, and even a complete, self-consciously all-inclusive film reboot in the aught years. Nimoy’s full acceptance of what he had helped to create reached its crescendo in 1984 when he directed Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, the first of several Star Trek projects he would produce or direct.

By then the name Star Trek was unstoppable for all parties involved: Star Trek III opened on June 1, 1984 in a staggering 1,996 movie theaters in the U.S. and Canada, the most movie houses to debut the same film on the same day in Hollywood history. It would gross $16.7 million in one weekend, and by the time the year had ended, the film directed by Nimoy would rake in more than $87.2 million worldwide. Not bad for a show dismissed by the brass at NBC as “too cerebral.”

Leonard Nimoy will be greatly missed by the science fiction fans of the world.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Revenge of the Nerds: Sciences Guys on the Big Screen; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review.

Interstellar: Science, Sci-Fi, and the Humanity Thing; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review.