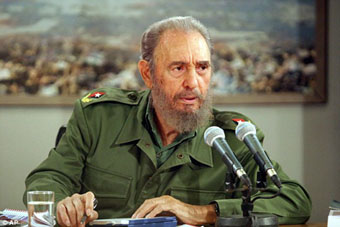

Image courtesy of CNN

The Split Screen of Castro’s Passing

| published November 28, 2016 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

It was inevitable. There would have to be that split screen—two almost comically differing reactions by people who not only speak the same language but speak it with precisely the same regional inflection. Some of those on either side of that split screen were related—cousins, distant perhaps, some closer, former co-workers, neighbors, one time friends, even siblings.

In Havana and all across Cuba, Saturday and Sunday became Days One and Two of what the government has decreed as nine days of mourning for the death of Fidel Alejandro Castro, who died quietly and peacefully late Friday night at the past-ripe old age of 90. Shops closed early, restaurants were shuttered, many schools will remain closed or operating under limited schedules for all of next week. Even baseball games were cancelled, some postponed for weeks. The arrival of a smattering of American tourists with wallets of dollars—travelers now free to visit the long isolated nation—meant little to those who grief was visceral and deep. People of all ages wept openly. Some stood in respectful silence in city squares.

By Monday, tens of thousands had formed a quarter mile long pedestrian line in Havana: mourners paying their respects to the singular political face of their lives as the procession moved slowly past the television cameras and reporters from around the world.

But in Miami, in Little Havana, and in similar pockets in Tampa and Sarasota, thousands celebrated in the streets in impromptu eruptions of joy for decades held in check by the defiant long life of the detested Castro—the arch nemesis who drove so many Cubans to flee the island over a span of more than 50 years. Their hatred of Castro always hinged upon the fact that he would one day—at long last—shuffle off this mortal coil and face his divine comeuppance, answerable finally for the ruination of generations of lives and a repressive order so entrenched it defied time, history and the arrival of a new millennia with global political and economic tidal shifts.

The split screen was also inevitable for the man with arguably the most familiar and iconic face of leftism and socialist working causes since Che Guevara. Guevara died young, at age 39, locking his face in time and sealing his doom as a logo, a t-shirt design, a pop culture avatar. Castro would suffer no such rock & roll marketing fate. Indeed after decades, Castro showed signs of devilish immortality, once the very figure of raging, cutting edge Marxism, but eventually the ragged caricature of its seething anger, constant resentment, and abject failures. He never once openly questioned his adherence to a crumbling economic and political philosophy even when his biggest patrons—the Peoples’ Republic of China and the Soviet Union—tossed their leaflets and party handbooks into the dustpan, picked up their collective baggage, and moved on.

The iconic and irascible dictator outlasted nearly a dozen American presidents, almost all of whom—save for perhaps current chief executive Barack Obama—had such a heavy ax to grind against Castro they uniformly endorsed an enduring sub-branch of foreign policy. Economic pressure, travel bans and covert ops became a permanent reminder of the Cold War at its worst and its best, including a salient military presence with constant eyes on an island 90 miles from U.S. shores and the decision—decades ago in a different geopolitical day and age—to place the American military’s Central Command in Tampa, where rapid responses could be executed with lethal swiftness.

The firebrand Castro also survived multiple assassination attempts, multiple coup attempts, and an invasion by heavily armed anti-communist insurgents at the Bay of Pigs. That doomed 1961 invasion—code named Operation Zapata, and using a paramilitary contingent of exiles known as Brigade 2506—was planned and coordinated by the CIA and the Pentagon and rammed onto the desk of the new U.S. president John F. Kennedy. It was a fiasco. It not only proved to be an embarrassment for the United States, but almost certainly played right into Castro’s hands, strengthening him politically at home and emboldening him to participate in the most dangerous game of roulette ever played out with nuclear weapons by the superpowers.

In the summer of 1962 Castro agreed to allow Soviet missiles to be emplaced on Cuban soil, a fact not quite fully discovered by American analysts until October of that year, when high resolution photos taken from the underbelly cameras aboard U2 spy planes revealed the extent of the Kremlin’s dangerous gambit. The resulting crisis took the world closer to nuclear war than even before, or since. In the end, Kennedy outmaneuvered Khrushchev, helping to diffuse the crisis, but it cost JFK—and most U.S. presidents ever after; Kennedy privately assured Castro that the U.S. would not engage in any more schemes for invasion. The Soviet Union packed up its rockets and rocket launchers and took them back to Russia, and Kennedy later pulled a squadron of mostly obsolete Jupiter missiles out of eastern Turkey.

In an ironic twist, Castro was cut out of the deal, a fact not lost on the leader whose ego matched his cruelty and his dedication to annoying the Americans at every turn.

The dictator who outlasted 11 American presidents, five Soviet premiers and one Chairman Mao defied time by surviving deeply into advanced old age and by stubbornly, even ruthlessly, clinging to the levers of absolute power. Like Spain’s Generalissimo Francisco Franco and Paraguay’s General Alfredo Stroessner—ultra-rightists both—Castro the ultimate leftist arrived at the pinnacle of political power and military control and never left it again unguarded, trusting few, jailing or eliminating those who posed a threat even through mild ideological disagreement, and crushing all forms of expression save for those approved by him alone. In the pantheon of dictatorship’s longevity, Stroessner held the record at 35 years in power. But by the middle aught years, Castro sealed that dubious title, and may yet retain it for the ages depending on the life of Kim Jong-un.

Celebrated by leftists and socialists worldwide for his introduction of universal literacy, educational reform and national healthcare, he was equally reviled for his caustic, bombastic disregard for human rights, including the systematic extinguishment of political dissent, the erasure of religious expression, complete control over the press, the arts and literary expression, and an ironclad ban on freedom of assembly—unless, of course, it was Castro himself who spoke as the headline act. Castro coldly and savagely rounded up his political opponents, tossing most into jails where they would languish for decades. Indeed, in the name of Marxist-Leninist purity, Castro may have imprisoned a higher percentage of his own people than any nation save for North Korea.

As a quid pro quo for decades of heavy Soviet economic backing of his impoverished finances—food, wheat, technology, weapons—Castro was compelled into foreign adventures, acting as a Soviet proxy in wars in Africa and Central America. Cuban soldiers fought and died in wars too grimy, too humid, or too unpleasant for Russian soldiers, but the symbolism of those Cuban infantrymen in places like Namibia, Nicaragua and Angola further angered Castro’s most vehement opponents, weary of hearing his more-or-less continuous 40 year harangues against American military interventions in Vietnam, Grenada, Panama, Kuwait and Bosnia.

Eventually, Castro became such a detested dictator that even many American leftists shunned his legacy, preferring to explain his deeds away as an aberration, not the norm of revolution and socialism.

Still, a million or more Cuban-Americans are divided, almost entirely along the familiar American generational pattern of fracture—older Cuban-Americans celebrating the death of a man they considered the embodiment of evil, younger people of Cuban dissent shrugging their shoulders and saying it was time to close the chapter on such grudges long ago.

That citizens of the United States are divided is no secret. Indeed, there is an irony to the parallel stories in the news, as Jill Stein’s Green Party—flush with the needed cash—files the paperwork to begin an election recount in Wisconsin, with the high likelihood of similar recounts in two to three additional states. The vanquished Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton and her top supporters and surrogates had mostly steered clear of the notion of recounts, but now embrace the project as essential to the clarity of democratic processes. There is irony too in the fact that Hillary Clinton’s most formidable opponent in the primaries and caucuses was Bernie Sanders, the Vermont Senator who often describes himself as a Democratic socialist, precisely the sort of American leftist who in the 1960s and 70s celebrated Castro as a heroic leader.

Castro’s passing comes just as President-elect Trump considers who he will insert into the top spot at the State Department. Trump has said that he regards Obama’s thaw in U.S.-Cuba relations a major policy misstep, second only in destructiveness—arguably—to the complex deal brokered by John Kerry between the United States and Iran. In recent days Trump has intimated that he will nix Obama’s template of rapprochement with Cuba, and possibly consider rebooting the long program of economic sanctions and restrictions against the island nation.

On the other hand, even conservatives of the Cold War generation now agree that Trump has a rare historical opportunity to close one chapter and begin another: Raul Castro has shown signs—limited, coded—that he wants to move carefully toward reform in Cuba. Cuba could be for Trump in 2017 what China was for Nixon in 1972: an opportunity for all parties involved to start afresh. Such a move would undercut any attempts by an emboldened Vladimir Putin to inject Russian influence into a post-Fidel Castro Cuba.

Raul’s previous entreaties to Washington seemed genuine, but were typically met by scorn from semi-retired brother Fidel, who would often rail against any compromise with the United States in vitriolic editorials in the state-run newspaper. Under such circumstances even Obama’s generosity was scorned, as Raul would often stress that Cuba was to remain a staunch bastion of Marxist-Leninist philosophy and practice no matter what olive branches the Americans offered. But now Fidel is gone, and Raul can take the next logical steps.

As tens of thousands stood in an now seemingly interminable line which winds its way for through Havana—each person walking past giant photographs of Castro’s face—reporters from scores of countries set up shop inside and around their satellite trucks and mobile television studios, bracing for the heavy artillery retorts from the 21-gun salutes fired each hour on the hour. Those guns have been a part of everyday life in Havana for decades, positioned along the seawalls and aimed vaguely at the bay and the ocean—violent tools of resistance if the Americans or their allies ever decided to attempt another invasion.

Per his wishes, Fidel Castro’s body was cremated on Saturday afternoon.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Fidel Castro Dead at Age 90; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; November 26, 2016.

The United States, Cuba, Democracy & Dissent; Earl Perkins; Thursday Review; April 12, 2016.