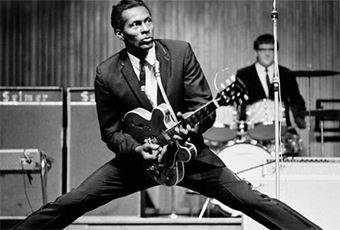

Image courtesy of University of Missouri

Chuck Berry Dead at Age 90

| published March 19, 2017 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

He was, and still is, widely considered the Father of Rock and Roll, and the innovator and guitarist who singlehandedly merged multiple streams of music—country, R&B, gospel, jazz, and blues—to create what quickly became known as Rock and Roll.

His songs have also become some of the most durable and iconic of generations of pop and rock music lovers worldwide.

Chuck Berry, songwriter and performer of such classics as “Maybellene,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” and “Johnny B. Goode” died this weekend at age 90. He passed away at his home in Wentzville, Missouri.

Berry was not only arguably the inventor of the musical form known as rock and roll, he was one of rock music’s earliest practitioners of the use of the electric guitar—the developer and composer of distinctive guitar licks and chord progressions which became the gold standard by which almost all other rock musicians would adhere. His guitar hooks and rapid-fire rhythms, which were merged seamlessly with a fusion of country twang, swaying gospel, hot jazz and traditional blues, cast wide multi-generational influence over rock and roll, shaping the sounds of groups and performers as diverse as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys and Steve Miller Band, The Who and Fleetwood Mac, Van Halen and Bon Jovi, Smashmouth and The Strokes.

Berry was also one of rock and roll’s most prodigious stage performance innovators, radically shifting the art of “performance” to a far more exuberant form of showmanship and physical theatrics, and paving the way not only for immediate successors like Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bill Haley, Buddy Holly, and Little Richard, but also the Beach Boys, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

Indeed, some music critics and historians suggest that Berry developed a musical form that the Baby Boom kids and teens of the mid-1950s didn’t even know they were in search of—music which ignored racial differences, upended musical conventions, broke with their parents’ collective musical tastes, and—perhaps most essentially—made them want to dance. His music was uninhibited, irreverent, and fun.

Berry was born Charles Edward Berry on October 18, 1926 in a middle class but African-American neighborhood of St. Louis. His earliest musical influences included the gospel music of predominantly black churches, a form of upbeat and twangy country music not yet even known as rockabilly, the hot jazz often performed in nightclubs in St. Louis, and the ancient thread of rhythm and blues as practiced by such writers and performers as Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Son House, and Lead Belly.

Originally schooled in hairdressing and cosmetology, for which he earned a college degree, his skill with the guitar and his love of music proved stronger than his interest in cutting hair. His ability to appreciate and immolate varying styles—even country music and western sounds—led him to join up with several local bands in the early 1950s, notably Sir John’s Trio, a regionally renowned band fronted by Johnnie Johnson but soon heavily influenced by Berry’s musical style, performance wit and guitar skills. Berry and the group played in nightclubs and venues frequented by both black and white audiences.

His abilities and power quickly led him to Chicago and into the orbit of one of his childhood icons, Muddy Waters. Seeing the raw talent and natural stage presence of Berry, Waters in turn dragged him immediately to the studios of Chess Records and owner-manager Leonard Chess. Chess listened patiently to Berry and his back-up performers run through an early version of a song called “Ida Red,” which Berry had begun to pen months earlier—a tune about a fast car and a girl. Chess recommended that they speed up the song and shift gears by tossing in faster bass rhythm (with Willie Dixon on bass) and rapid guitar chord changes.

Recorded for keeps on May 21, 1955, it may have been the singular moment when rock and roll was born. Len Chess, whose instincts about such things usually proved prescient, insisted the song be renamed “Maybellene,” and the rest—as they say—is history.

Thanks to positive reviews and a promotional nudge by radio disc jockey Alan Freed, “Maybellene” burst onto the Billboard charts, rocketing to number 1 on the R&B charts and number 5 on the pop list. The infectious tune was even picked up by country music stations across the nation, some of whose programmers and deejays—hearing the sharp enunciations, the non-bluesy lyrics, and the lack of a regional accent—mistakenly thought the singer was white.

Berry recorded and performed hundreds of songs and established himself firmly as a rock and roll icon with huge hits, from “School Day” to “Johnny B. Goode,” from “Rock, Rock, Rock” to “Sweet Little Sixteen,” from “Roll Over Beethoven” to “Go, Johnny, Go.”

“Roll Over Beethoven” was reworked and rebooted famously twice, first by the Beatles on their second album, and again more than a decade later by Electric Light Orchestra. His songs have been reprised in movies and television hundreds of times, and groups as diverse as the Beach Boys and Van Halen have paid homage to the Father of Rock and Roll with well-crafted remakes of Berry’s most famous tunes.

Berry’s other notable hits included “Reelin’ and Rockin,” “Nadine,” “No Particular Place to Go,” and “My Ding-a-Ling,” which reached into the top 20 on the charts in 1972.

Berry never let age enter into the equation of his legacy or his love of music; he performed regularly well into his middle 80s, even wowing audiences in his octogenarian years by performing his famous duck-walk moves on stage and still showing that he could handle an electric guitar as well as Brian May or Keith Richards or Jack White. Rolling Stone called Berry the sixth best guitarist in rock history.

Aside from a lifetime of awards and recognitions for his work, his innovations and his creativity, he is one of only five musical artists whose music has travelled in recorded form into deep space: “Johnny B. Goode” is etched upon the solid gold record discs propelled into space aboard both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. That means that someday in the presumably distant future aliens of some faraway world will get to listen to the sounds of the man who may have singlehandedly invented rock and roll. Let’s hope they have a dance floor on that planet.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Jazz Clarinetist Pete Fountain Dies at 86; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; August 12, 2016.

George Martin and the Beatles First Record; Kevin Robbie; Thursday Review; March 18, 2016.