Cross Creek and the Literature of Paradise

By Earl Perkins | published Monday, October 14, 2013 |

Thursday Review Associate Editor

"Somewhere beyond the sinkhole, past the magnolia, under the live oaks, a boy and a yearling ran side by side, and were gone forever."

--Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, from The Yearling

Home was among the thickest conglomeration of mosquitoes and deer flies in the backwoods of North Central Florida, an extremely inhospitable residence for man and beast. There were really only three sets of folks who chose to live there back in the day—Crackers, one extended black family and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. The term Cracker came from cowboys having to round up wild cattle throughout Florida, and there was plenty of whip cracking in the early days because there were no fences.

Rawlings, who was born in Washington, D.C. in 1896, had already been writing for newspapers in Louisville, Kentucky and Rochester, New York, but in 1928 she made a decision that would forever change her life and touch millions of readers' lives across the world. When her mother passed away, she chose to take the small inheritance and buy a 72-acre orange grove near a place locals called The Creek—Cross Creek, a small slip of water which connected Orange and Lochloosa Lakes—where she could find isolation while writing about the people, plants and animals she encountered. Though she had been writing professionally for years, her real career started off with letters to an editor friend at Scribner's, the legendary Maxwell Perkins, who encouraged her to write a book that would contain the stories concerning the people and surroundings at Cross Creek.

It took quite a while for the locals to warm up to Rawlings—they weren't very trusting of newcomers. Outsiders were mostly looked upon with suspicion, which was probably a good policy under the circumstances: locals fished and hunted according to the moon, stars and tides, and with almost no concern about government hunting and fishing seasons or licensing. The remoteness of the area also meant that there no witnesses as to whether dynamite may or may not have been used on occasion. And, common in some rural parts of Florida, there were moonshining operations to consider, which would certainly be looked upon with umbrage by certain authorities. These were people who lived off the land, a hardscrabble life, mostly folks from Georgia who had migrated south looking for a better life.

The area had barely changed since prehistoric mammals lived on the Florida peninsula. Creek Indians and a few Seminoles farmed the area from the mid-1700s, but the white man drove them south in 1823. The Crackers then moved in the form of trappers and hunters, followed in the 1880s by railroad pioneer Henry Plant who was in the process of running tracks from Jacksonville to Tampa. The new rail route cut through Marion and Alachua Counties, along the west shore of Orange Lake and just six miles from Cross Creek.

Those were heady days, for thanks to the railroad, a bit of civilization was coming to the creek. Predictably perhaps, the land developers appeared before the right of way was cleared. These were silver-tongued salesmen, and they found willing victims from up north who were armed with ignorance and optimism. The advertisements spoke glowingly about the lush land of sun and opportunity, a place where hard-working people could make a fortune. They built houses and planted orange trees everywhere, knowing they'd soon be filthy rich. But devastating freezes at the turn of the century wiped out many of the orange groves and, with them, the new settlers' dreams, forcing them to flee back north. The only remaining humans were old Florida Cracker families who were smart enough to continue to live off the land, just as they before the speculators and investors had arrived.

There were the villages of Island Grove just to the east and off to the west was Micanopy, named for the chief who led the Seminole Indians in the Second Seminole War.

A personal aside: a great aunt of mine left Millwood, Georgia, with her family in a covered wagon soon after 1900, moving south to the land of obvious opportunities. She worked hard all her life and she certainly prospered if you consider raising a fine family a mark of success. She didn't quite reach her 103rd birthday, but she gave it her best shot. Also, my father's mother was raised on a farm outside Reddick, which was a wide spot in the road near present-day Ocala. She left for Jacksonville around 1920, and although relatives were on their way to pick her up, she just couldn't wait. She came out to the hard road at a fast walk, and headed north—on foot—along what would become U.S. Route 301. She never would return to Reddick, even refusing to visit cousins outside Trenton, because they lived on a farm.

But let's get back to Miz Rawlings and her story. She received the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1939 for writing The Yearling, a story about a boy who adopts an orphaned fawn. The book was eventually turned into a movie which was seen by millions, propelling Rawlings to stardom. Best known for writing The Yearling and Cross Creek, Rawlings sometimes portrayed the locals in a harsh and unflattering light. She even lost a lawsuit concerning that matter, eventually leaving the area and moving to a home she'd purchased in St. Augustine. She felt betrayed by the suit, because she truly had great respect for the people and their grit, self-reliance and hard-working resourcefulness. She loved everything about the creek, but especially all the wonderful people and their stories.

Some of Rawlings’ other works, less known than her Pulitzer winners, include The Sojourner and The Secret River, as well as Cross Creek Cookery (1942), an expansion of sorts of one of her most colorful and interesting chapters from Cross Creek called “Our Daily Bread.”

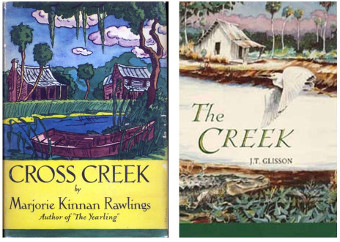

Depression and artistic frustration dogged Rawlings her entire career. But that meant she would fit right in at the creek, because it was the kind of place where people were allowed to be themselves. Many folks have certainly read Cross Creek through the years, but another book you might want to consider is J.T. Glisson's The Creek, originally published by the University Press of Florida in 1993. All the characters had titles—meanest, laziest, most pregnant, best catfisherman. Oh, it's all there; a simple and fair-minded story that talks about the colorful locals and gives an incredibly in-depth history of the region where Glisson grew up and as a child was a protégé of Rawlings'. It's possibly one of the finest books ever written about a single region of Florida.

But it was Rawlings’ two most famous books that brought attention to perhaps the most primal and remote place imaginable before the advent of the now ubiquitous interstate highway. Her award-winning books still read with a freshness and clarity often missing in contemporary writing.

How else would you know if you wanted to see Cross Creek back in the very early 1900's that you first needed to cross a river into a strange paradise of palmetto thickets, hammock and lush drapes of moss? I thought that was where you went when you were bound for glory land. Anyway, that was where you'd find the man with a mule-drawn wagon, and he'd load up you and your luggage and you'd head up the trail through several miles of dense hammock.

But then I guess I'm starting to kill the story for you. I'm just pretty thrilled that when I was a youngster my father drove me all over and made me meet hundreds of people. He said someday they'd all be gone, and everything we saw would be totally different. I really didn't believe him at the time, but he was right.