photo courtesy of Thursday Review

Equifax Data Breach May Be

Most Serious in U.S. History

| published September 14, 2017 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

So long to your most sacred personal information—or so say the experts in the wake of a data breach at the Atlanta-based credit reporting agency Equifax. According to federal law enforcement, there is an 80% chance that cyber thieves may now have the basic building blocks of your most critical information, including your full name, social security number, home address and past addresses, and birth date. The result could be damaged or at-risk credit for most Americans, ironic considering that all that critical data was stolen from a firm for which the central mission was to monitor and safeguard credit.

In the immediate and widely publicized aftermath, Equifax, Experian and Transunion have been overwhelmed with calls and online requests by consumers seeking to “freeze” their credit—a process by which any new requests for lines of credit or loans for an individual are automatically prevented. Despite the fee of $5 to $10, millions of people have jammed phone lines or overwhelmed online websites requesting a freeze be put in place on their accounts.

Equifax’s top executives, including CEO Richard F. Smith, have been notably mum on the subject after an initial web video in which Smith offered a tepid, shaky apology to consumers. At least three Congressional committees have demanded public hearings, watchdog and public interest groups are calling for Smith and others to resign, and consumer groups are demanding that Equifax be held solely and categorically responsible for any financial damages or losses as a result of the breach. The theft of that information could haunt the American economy and consumer confidence for decades.

Cyber experts now suggest, however, that it was merely a matter of time.

Over the last five years news regarding major data breaches has become sadly more common, each new cyber intrusion adding to the increasingly wide ripple effect within the economy. Retail giant Target had set the bar very high when it was revealed in 2014 that its data breach had allowed hackers access to the credit card information of some 53 million customers in the United States and Canada. Similar cyber intrusions hit other retailers in that same 12 month period—Michael’s, Home Depot, Hilton Hotels, Neiman-Marcus.

Likewise, data beaches impacted the University of California huge network of hospitals, labs and clinics in 2015, exposing the medical records of 4.5 million patients. A similar cyber 2014 intrusion, triggered by a vulnerability known as Heartbleed, brought the theft of another 5 million sets of medical records and employee files from Community Health Systems (CHS), a management company which handles administrative functions and recordkeeping for more than 100 hospitals in the U.S. In 2014 Anthem Incorporated revealed that hackers—most likely in China—had breached the insurance and medical records giant and hauled off with the social security numbers, addresses, emails, and cell phone numbers of roughly 75 million customers and patients.

A June 2015 cyber breach of the Office of Personnel Management may have resulted in the theft of personal information for some 19 million people subjected to various forms of official U.S. government background checks—the sort of deep data which may also include credit histories, criminal records, property and vehicle ownership, and all places of residence of millions of military and civilian personnel.

Then there was the infamous Sony hack attack—a massive intrusion into the network of one of the world’s largest entertainment companies, a cyber breach which included the premature release of major movies, the complete crash and takeover of the company’s huge intranet and database, theft of company records, exposure of sensitive internal emails, and even the revelation of salaries of employees and bonuses paid to executives. Lawsuits continue to fly back and forth in the wide wake of the Sony debacle. And that may have been just a foretaste of the problems now faced by HBO and other media giants, now revealed to have had their own data breach incidents. The Sony breach is believed by some experts to have been the work of North Korean hackers, through this theory remains in dispute.

But as large and disruptive as they were, those news-worthy breaches as Target and Sony may pale when compared to the data breach only recently announced by credit reporting giant Equifax.

Last week, after months of delays, Equifax revealed for the first time that it experienced a massive cyber intrusion—made possible by a vulnerability in its online code—which allowed hackers access to the credit records of roughly 143 million Americans, or more than half of the total U.S. population.

Unlike the data breaches at Target, Home Depot and Neiman-Marcus, which required merely that customers obtain new credit cards and a blanket promise of close credit monitoring, the Equifax cyber breach has neither an easy-to-grasp defense nor ready-to-deploy solution for consumers. In fact, the Equifax data breach is so bad, and carries such far-reaching consequences, that many cyber experts and credit card analysts suggest that the long term effects could have serious effects on the U.S. economy for years.

The biggest danger in the immediate aftermath of the Equifax data breach: outright identity theft, on a grand scale.

More than a specific card number or a cell number, which can be quickly changed or swapped in the event of a problem, the data collected by agencies like Equifax include those details which are permanent, fixed, and enduring, such as date of birth, place of birth, social security number, and home addresses. Equifax also stores driver’s license numbers and, in many cases, place of employment. And because Equifax (like its fellow credit reporting firms Experian and Transunion) is in the primary business of tracking the details of your credit activity and payment history, its records also contain the detailed patterns of your consumer behavior—how you pay for your home or apartment, your cars, your vacations, and how you pay almost all of your monthly bills, from cell phones to cable TV, from your account at JC Penney to that Texaco credit card.

The risk, according to many experts, is that the Equifax breach will lead to a decade or more of persistent identity theft impacting many—if not all—of the 143 million people whose credit records are now in the hands of unknown hackers. And that means that those same 143 million American consumers must now ramp up their own efforts at vigilance—even more closely watching their accounts and their statements for any suspicious activity and any unusual movement. Even a tiny unexplained expense on even the most obscure credit card could be a sign that someone, somewhere, is testing the limits of your vigilance.

Worse still, the basic data contained within the range of stuff hacked from the Experian database means that identity thieves—who may not be the same people who stole the information in the first place—have the ability to create an entire parallel universe of identities, with the unfortunate potential for one, or two, or even three new identities for any single individual whose personal data was stolen.

That parallel universe of stolen identities can come in a variety of forms, including the creation of phony identities specifically for medical use (for real but expensive medical procedures and treatments) and for medical misuse, such as outright insurance fraud. The trove of personal data stolen from Equifax can also be used by the growing number of hackers filing phony tax returns—a persistent and metastasizing problem for which the IRS has shown little ability to mitigate against (even the seemingly obvious permutations, such as the tens of thousands of American citizens wanting their tax refunds sent to banks in Portugal, Romania, Hungary, and Slovakia; or the hundreds of tax refunds sent to the same address in, for example, Tampa, Florida).

Like its fellow firms Experian and Transunion, Equifax deals in a heavy daily flow of seemingly routine information, including the aggregate monthly credit card activities of all its 143 million clients. If you have ever seen a readout of your credit report, you know that it shows all interactions with any company or agency with whom you have an open line of credit or with whom you have done significant credit-related business: cell phone companies, land line providers, cable TV or satellite, high speed internet providers, storefront retailers, gas stations, electric and gas utilities, water companies, online retailers such as Amazon, and lenders for cars, houses and major purchases.

This means that the end users of your stolen information have not only your significant facts (birth date, social security number, current and past address), but also a broad look into your overall financial health and buying patterns, giving them the canny ability to “replicate” who you are in even ways hard to detect by others in the financial industry. A person who lives in Pittsburg, for example, and has had their personal data stolen from Equifax, might discover years later that a “parallel” version of them has been staked out in Los Angeles—same name, same social, same birth date, same history of good credit, apartments, homes, cars, lenders. Since the electronic paper trail is accurate and complete—right up to the facts that your car loan came from GMAC, you have credit cards for BP, Lowe’s and Macy’s, and you once had a Pennsylvania driver’s license, even a banker or lender in LA would have difficulty detecting anything amiss.

Adding to the misery for everyone involved, Equifax has offered little in the way of explanation as to why it took the company weeks to report the cyber intrusion to the FBI and other law enforcement, and why it took the firm more than a month to inform consumers of the breach. Experts point out that the sort of data stolen from the Equifax cache may have been sold, resold and deployed with the first days or weeks to the highest bidders in more than three dozen countries. The breach occurred, according to company analysts, between mid-May and mid-June, but was apparently not discovered until late July. Even then, the company remained mum on the subject until just a few days ago—well into September and too late for some unlucky consumers whose data may have already passed from the hands of the hackers to those with more serious criminal intentions.

Equifax has said, in generally vague terms, that the breach came about as a result of a long-undetected “website application vulnerability,” the key word “vulnerability” meaning an unlocked window or door somewhere within the vast electronic firewalls created to keep hackers out of such places. Like other cyber breaches—Target, Michael’s, Sony, even the IRS—such micro opportunities allow for macro theft if these vulnerabilities and weaknesses are discovered by criminals first, and not by company security experts. With more online activity now shifting to mobile applications—meaning smart phones and handheld devices—the complexity of making new forms of code foolproof becomes even more daunting. Few companies can eschew the public shift toward mobile apps, but few can afford the staggering cost of policing every line of code or monitoring every portal for digital access, especially the kinds of convenient access offered by handheld devices.

Some private security firms, along with some investigating the Equifax breach, say that the company had been warned about several potential flaws in its codes and scripts as early as last year, and ABC News and other media have reported that the specific vulnerability which allowed the current breach to occur was known by some within Equifax at that time.

Meanwhile, numerous members of Congress have said there will be hearings into the mess as more facts become available, and some top Equifax execs are already under pressure from consumer groups and stockholders to resign. One area of concern to regulators now looking closely at the unfolding mess: several top Equifax executives dumped large quantities of their own company’s stock during the brief period between when the breach was known within the firm and when it became public information only days ago. Though company spokespersons claim those same execs knew nothing of the breach at the time they sold their substantial blocks of shares, the news that top managers were dumping their own company’s stock has infuriated consumer groups and watchdog groups alike, and has stoked the ire of some in Congress who only says earlier were willing to extend Equifax the benefit of the doubt.

On social media, tens of thousands have taken to berating Equifax’s seemingly lukewarm and slow response to the widening problem. Equifax has offered one year of no-strings-attached credit monitoring and identity theft protection, but many are skeptical of that limited period of scrutiny, pointing out that the stolen data—birth dates, addresses, social security numbers, and credit histories—will remain viable and useful to thieves and hackers for years, even decades. Several major consumer groups have called for Equifax to offer free credit monitoring and identity theft protection for all of the 143 million now impacted…for life. Period.

Others have said that Equifax should be held responsible for any and all financial losses which come as a direct result of the breach, and some in Congress have demanded that Equifax quickly rethink the legal clause hidden in its agreement to monitor credit, a fine print catch which says the company cannot be held accountable for any financial injuries to the consumer after the one year of credit monitoring has expired.

Despite more than $200 million in Washington lobbying by the big three credit agencies, even many Republicans in Congress—previously agreeable to fewer regulations on the credit reporting firms—are now are now shunning Equifax for the deep damage the company has done to consumer confidence, and the decades of uncertainty now injected into the seemingly simple business of getting a loan or a credit card from banks or retailers. Republicans, traditionally predisposed to less regulation, are under the same pressure from their constituencies as Democrats.

Consumer groups and law enforcement agencies have taken the unusual step of warning all Americans to take very seriously the potential for harm, advising everyone to assume the worst. Among the quick defenses available to almost anyone: obtain a current readout of your credit report immediately. These can be requested free of charge as often as once per year. In addition, many experts suggest imposing a “freeze” on your credit. This will prevent anyone from opening up new lines of credit or seeking loans using your name or identity. Burnish this by personally contacting your bank, your mortgage company, and—if necessary—any or all providers of credit cards, from Visa to MasterCard to American Express, from Wal-Mart to Kohl’s to Best Buy.

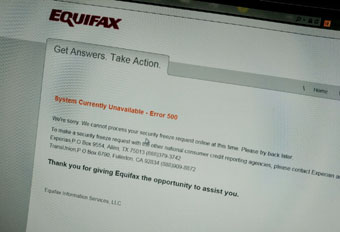

But the step of freezing credit could take days, weeks, even months, as all three major credit agencies cope with a tsunami of phone calls and online requests to freeze credit. Websites have been stuck or have crashed, and tens of thousands of people report getting a standard recording when they attempt to call. At Equifax, the “online chat” option is “unavailable.” Those able to reach a live person do so only after long on-hold waits reportedly exceeding 90 minutes. Those able to navigate through the website often run headlong into a screen which says “system currently unavailable” (see our photo).

Many Americans stuck toward the end of that long queue are wondering if they can properly safeguard their credit before thieves—surely now working to make the stolen data profitable in criminal ways—can wreck their credit scores and their financial health.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Cyber Attack Targets UCLA Hospital System; Keith H. Roberts; Thursday Review; July 18, 2015.

Taxpayer Information Stolen From IRS Website; Keith H. Roberts; Thursday Review; May 27, 2015.