Images courtesy of Reuters/U.S. DEA

Fixation on Tunnels May Have Been El Chapo’s Downfall

| published January 9, 2016 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

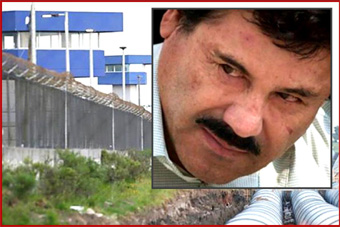

For six months he was—again—the most wanted and most hunted man in the world. But this past week Mexican police, Mexican Marines and Mexican Special Forces units, heavily armed and spurred by new intelligence information from key informants, caught up with drug lord Joaquin Guzman Loera, also known as “El Chapo” or simply Guzman. This week's raid was bloody and violent--several suspects were killed and several police officers wounded.

Guzman, we now learn, was captured when Mexican authorities decided to cease and desist from physical chases of El Chapo—almost all of which have failed over the years—and turned instead to tracking the activities of the best tunnel engineers in Central America.

Guzman and his crew are, of course, now infamous tunnel builders.

While serving the first year of a life sentence in Mexico’s most secure prison near Toluca—about a one hour drive west of Mexico City—Guzman escaped by way of an elaborate and sophisticated tunnel apparently dug right under the noses of prison officials and police. The tunnel, which connected his cell to a small building more than a mile away, was outfitted with electrical lighting and ventilation, and contained a narrow rail track upon which a custom-fitted, gas-powered motorcycle was used to pull carts of dirt. Guzman himself may have used the motorcycle to speed up the final moments of his daring July 2015 escape.

Investigators later learned that Guzman’s escape was made possible in part through copies of detailed land surveys, construction diagrams, and even a complete set of blueprints of the prison, purchased after hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of bribes were paid by Guzman associates to officials in the prison system and the government.

Guzman’s high-profile escape was a major embarrassment for the government of President Enrique Pena Nieto, and for the offices of the Attorney General and top prosecutors—all of whom had been warned by U.S. intelligence agencies as early as 2014 that there was evidence suggesting that Guzman’s operatives may have been planning an escape, specifically by use of a tunnel.

Since Guzman’s escape on July 11, Mexican authorities have been engaged in a round-the-clock effort to recapture him. The work has led to several close calls, including one encounter months ago in which police believe that El Chapo may have sustained minor injuries. But despite scores of arrests, hundreds of interrogations, and a half dozen chases (including that near-capture which took place in Durango where El Chapo was meeting with other drug cartel operatives), Guzman has remained slippery and on the move.

But weeks ago Mexican officials learned that they had identified a key facilitator of Guzman’s elusiveness: one of his chief tunnel engineers. That critical lead, according to U.S. and Mexican officials, allowed police to anticipate Guzman’s next possible move by factoring-in his penchant for tunnel escapes. Guzman has returned to his home turf in Sinaloa, where law enforcement then tracked the movements of the known tunnel expert. This led officials in Mexico City to couple reliable intelligence regarding Guzman’s last known position in Sinaloa to the movements of the tunneller and his operatives, leading police to a house in the town of Los Mochis.

Operating quietly and out of sight of most locals, Mexican Marines and Mexican Special Forces units sealed off the town’s drainage system, blocked known underground access points, and stealthily encircled all reasonable routes of escape…then they made their move. According to Mexican police, as soon as the raid began on the house, Guzman immediately made his way into a tunnel and into the town’s drainage system. He was captured as he emerged and attempted to get into a car parked in a prearranged location. Shots were fired, a brief gun battle ensued, but Guzman and about seven others were immediately arrested, and El Chapo was quickly handcuffed and taken to a waiting helicopter which whisked him out of the Sinaloa state and back to the maximum security prison at Toluca.

According to Mexican officials, a deep analysis of both U.S. and Mexican intelligence revealed that Guzman was in the process of outfitting at least a dozen homes in various cities with tunnels and escape systems, including elaborately mapped plans for using drainage systems, canals, utility conduits and basements as portals for evacuation. There was also evidence that he was arranging for fully-fueled vehicles to be parked in strategic points near all of the homes being equipped with tunnels. This enabled authorities to watch the movements of all known tunnel engineers and builders, especially those suspected of aiding the drug cartels with tunneling operations along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Based on tips from a few locals, undercover police had been watching a house in Los Mochis, in Sinaloa, for weeks when late at night on January 7 a contingent of SUVs pulled up in front of the home and several hooded people moved quickly into the house. This gave authorities time to get the Marines and Special Forces units in place around the town.

Strangely, vanity may have also played a role in Guzman’s capture. An apparent fan of true-life and fact-based films and action-adventure movies, Guzman had expressed hope recently that he could participate in the production of a movie about his life. Authorities say that Guzman may have contacted several well-known Spanish-speaking actors and actresses, along with potential producers. This led to tips to police regarding Guzman’s movements in the days and weeks prior to meetings he had allegedly scheduled with possible filmmakers.

Since the late 1980s, Guzman has been the boss of the so-called Sinaloa Cartel. After the demise of Columbian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar, Guzman’s operation expanded rapidly. Guzman was caught and jailed in 1993, but escaped with the help of corrupt prison guards and supervisors in 2001. During the aught years, he consolidated control of Mexican and some Central American drug operations, often fighting a brutal and bloody war with rival gangs and law enforcement. During that decade, more than 100,000 people died as a result of the gang violence, much of it along the border between the United States and Mexico. Guzman maintained criminal operations in neighboring Guatemala, Costa Rica and El Salvador, where gang violence and criminal activity continues to this day. Guzman’s principal operations involve the distribution of cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines and marijuana into the United States and Canada, but his criminal reach also extends into parts of Europe, South America, the Caribbean, Australia and New Zealand. Officials in several countries believe that at the height of his power before his previous capture, Guzman’s Sinaloa Cartel was worth more than $20 billion and the El Chapo himself was worth $1.5 billion.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Arrests Made in Guzman Escape Caper; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; July 18, 2015.

Mexican Officials: We Were Warned of Guzman Escape; Thursday Review staff; Thursday Review; July 17, 2015.