When Hollywood Was Right

Book review by R. Alan Clanton | Monday, January 6, 2014 |

Thursday Review editor

A few days ago when film star Steven Seagal, known for his action-adventure roles often involving martial arts skills and physical strength, announced to reporters that he was considering a bid to run for Arizona governor, the news—while significant politically in the Grand Canyon State—sent few shockwaves through the world of political reporting nor through the mainstream chatter.

Seagal, who has already been deputized by law enforcement offices in several states, including New Mexico and Texas, told reporters that security along the United States’ long border with Mexico should be a priority. Seagal has frequently teamed up with real-life sheriffs and cops for his past and current movie and TV productions, including his recent collaborations with high-profile Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County, in Arizona.

For many Americans, these collaborations between Hollywood and law enforcement seem routine, and the merging of politics and entertainment across the broader spectrum, one could easily argue, is virtually complete. Well-known actors and actresses often float trial balloons to gauge their political chances or to simply stir the pot, and the recent photo-ops have been frequent: Ashley Judd, Brad Pitt, Alec Baldwin and Matt Damon have all talked openly of their interest in running for public office (in Damon’s case, perhaps it was enough that he ran for the U.S. Senate—and lost—in the fantasy/sci-fi movie The Adjustment Bureau).

Other Hollywood names are now as often associated with politics as with the movies that made them famous over the decades. Think of action and cop-film icon Clint Eastwood, or singer-songwriter Sonny Bono, or even Saturday Night Live’s Al Franken. Then there were action heroes Jesse Ventura and Arnold Schwarzenegger, each of whom became governors of major states (Minnesota and California, respectively). Indeed, one could create a fun parlor game of identifying how many cast members from Predator have run, or held, elected office. The general narrative now is one of a film industry dominated by liberals and social progressives, many of them in a state of constant public discourse and interaction about the issues of the day (think of Tim Robbins, Sean Pean, Alec Baldwin, George Clooney).

But there was a time when such a direct overlap between Hollywood and the voting public was rare, if not altogether unlikely. And on those few occasions when actors or actresses stepped in the zone of political conversation, they often arrived from the right.

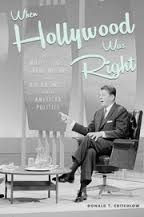

A new book by Donald T. Critchlow, When Hollywood Was Right: How Movie Stars, Studio Moguls and Big Business Remade American Politics (Cambridge University Press), argues that the mega-money business of motion pictures and TV has always found itself comfortable with shaping the outcome of American democracy. Indeed, Critchlow posits, our recent perceptions of the Hollywood establishment and the New York TV literati as claques of dedicated liberal thought and leftist activism are at odds with the actual track record—especially when viewed through the prism of Hollywood’s studio chieftains, often conservatives, and their business models for financial success.

Critchlow traces the early days of starpower in politics, including the career of Broadway and screen star Helen Gahagan Douglas, whose contentious re-election campaign for her U.S. House seat in Southern California pitted her against a young but aggressive and savvy Richard Nixon. Nixon’s victory in that bitter campaign would, in part, forge his combative style of campaigning for decades.

Later, in the same southern California milieu (and at about the same time that Arizona’s Barry Goldwater began his ascension within the GOP), the actor Ronald Reagan would collaborate with regional business interests and conservative activists to make the transition from Hollywood and TV into politics. Reagan’s style of outreach was formidable, and his likeability—carefully crafted and prosed as an outsider—opened the path for Reagan to challenge the popular California Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown. The actor was was regarded as a lightweight to politics, and Brown and his handlers underestimated the novice Reagan, but in televised debates watched by millions in California, the affable star of movies such as King’s Row and Law and Order pummeled Brown. Reagan won in a landslide, and the political upset was a game-changer—setting Reagan on a trajectory that some pundits assumed would eventually place him in the White House.

Nixon, too, learned—often the hard way—about the power of television to craft an image of success or failure. Early victories against Helen Gahagan Douglas and Jerry Voorhis galvanized his tough campaign style and combative approach to victory, but his debates against the young, handsome John F. Kennedy seemed to instantly redefine both the political process in the U.S. and the newly-established importance of television in the American home. (Entire books have been written on this subject, and I recommend Alan Schroeder’s Presidential Debates: Fifty Years of High Risk TV, Columbia University Press, which we reviewed last year in these pages).

There were, of course, collaborations between star-power and politics prior to Reagan, and Critchlow looks at the careers and political outreach of actors such as Robert Taylor (who once had political ambitions of his own), Barbara Stanwyck, Jimmy Stewart, John Wayne, Helen Hayes (all Republicans) and anti-New Deal critic Gary Cooper—actors often working closely with the savvy studio heads (conservatives like Cecil B. DeMille and Walt Disney) who shaped so much of what Americans enjoyed in their local movie theaters.

Critchlow’s book covers the formative and oft-overlooked years when the studio moguls worked, sometimes quietly, to shape the collaborations between their actors and the political processes important to them. Don’t let the whimsical, charming retro book cover fool you: Critchlow has meticulously researched his subject matter and his history, and each page is footnoted with copious references to his extensive research. The book is relatively small, and reads easily despite its academic prose.

This book is also an engaging and entertaining look at how some of the shrewd men in Hollywood worked with actors and actresses to reshape the Republican Party, and then help propel that newly energized conservative legion toward national political success. Critchlow’s book is an excellent and enlightening read.