A Letter From Hell: Part Two

By Kevin Robbie | published Wednesday, October 23, 2013 |

Thursday Review Contributing Writer

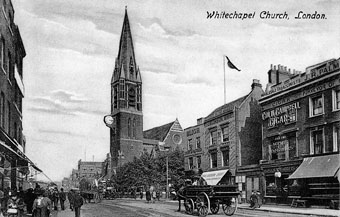

There are many aspects of the Jack the Ripper case which provoke debate to this day. One such topic is a series of letters received by the police and the Mile End Vigilance Committee, chaired by George Lusk. The committee had been formed by Lusk and other businessmen in Whitechapel in an effort to assist police in finding the killer, who had just claimed his second victim, Annie Chapman, at the end of August.

On October 16, Lusk had received a letter, postmarked the 15th, attached to a small box and wrapped in brown paper. The box contained the rancid remnant of a human kidney. The writer of the letter claimed to have eaten the other half of the kidney. The writer also asserted that he “took the kidney from one woman.” A woman, Catherine Eddowes, had been found murdered in Mitre Square on October 15. She was the fourth of the “canonical” victims of Jack the Ripper. One of Eddowes’ kidneys was missing, along with her uterus. Her face had also been mutilated.

Initially, Lusk was inclined to believe the letter was a prank. He kept the letter for nearly a week before showing it to the other members of the vigilance committee. They suggested showing the letter to the police. The words “From Hell” were prominently written at the top of the letter in large script. The letter appeared to be written in red ink. Was the writer trying to be melodramatic? Was the phrase chosen as an attempt to intimidate the letter’s recipient so as to cause him to back off the search? If the letter was authentic, the killer was certainly drawing more attention to himself. He was also attempting to conceal his identity because the letter was unsigned. Lusk held onto the letter for several days. He may have believed that the killer would target him for attack if Lusk revealed it to anyone. The writer certainly knew Lusk’s address. One could reasonably assume that since Lusk was working so closely with the police, he wouldn’t be giving out his address in public, at least not his house number. The letter ended with the words “Catch me when you Can, Mishter Lusk,” (original misspelled) implying the killer would strike again—and vanish—into the dreary night.

Another important distinction with the previous letters was, of course, the kidney. Doctors of that day lacked the technology to determine with certainty whether or not the kidney was cut out of Catherine Eddowes. It is possible. In addition, the previous letters had been mailed to the central news agency (CNA), a news distribution service in London. However, the “From Hell” letter was mailed directly to George Lusk. Sending letters to the CNA would imply that the writer had some knowledge of the workings of the press. If Jack was a denizen of Whitechapel, as police suspected, it is likely that he was poorly educated and he would be unaware of the existence of the CNA and its role as a supplier of news. Also, the letter was written by someone with a lower literacy level than the previous communications to the press. Another distinct aspect of the letter was its lack of a signature. Previous letters had been signed, purportedly by the killer. Jack may not have been in the habit either of writing letters or observing letter-writing etiquette such as signing one’s name. Such a distinction would be consistent with a killer who lived in Whitechapel.

And Jack did strike again. A period of five weeks ensued between the killing of Catherine Eddowes and Mary Kelly, the final canonical victim, on November 9. The murder of Kelly, also a prostitute, represented a peak of frenzy for the killer and has raised its own questions. For example, why was Kelly the only “Ripper” victim found indoors? Was Jack leery of being detected? The landlord’s assistant, Thomas Bowyer, found the body at 13 Millers Court. After knocking repeatedly on the door and receiving no response, he peered through a dingy curtain hanging over the window. Bowyer was both stunned and horrified by what he discovered and he left to report to his boss, John McCarthy. The shaken Bowyer told McCarthy what he had found and stated “I’ve never seen so much blood.” The two men returned to the address with the police. They found Kelly’s clothes neatly folded on a chair and her boots in front of the fireplace. She was wearing only a chemise. Was the killer a client, as Kelly was seemingly prepared to conduct business? Had Bowyer or McCarthy tidied up Kelly’s clothes out of a sense of pity? How did the killer leave the premises? Police found no obvious sign of egress from the scene and no one in the area saw anyone leave the premises. Why the five-week gap between the fourth and fifth murders? And there is the obvious question: why was Mary Kelly attacked so savagely?

According to police, Kelly’s face had been hacked almost beyond recognition. Modern attempts at facial reconstruction, if accurate, show that Mary Kelly was a very attractive young woman. As for her other wounds, police surgeon Thomas Bond filed an extensive report wherein he described the condition of the corpse: “The abdominal cavity was empty of its viscera; the heart was missing; the breasts had been removed using circular cuts; neck tissue was severed down to the spine; right thigh denuded of flesh to the femur, which was exposed; the torso had been opened up from the sternum to the pubic mound…..” The complete description of the mutilation of Mary Kelly is much longer. The doctor also noted that Kelly’s thigh tissue and some of her internal organs were lying on a table beside the bed. Other organs lay underneath her head like a gruesome pillow. Apparently, Jack had plenty of time and he made good use of it. In addition, the report mentioned significant blood splatter on the wall near the bed. Dr. Bond concluded that the splatter occurred when Kelly’s carotid artery was severed, as was the case with the previous victims. The doctor further noted that underneath the bed he found a pool of blood approximately two square feet in size.

After each killing, Jack the Ripper seemed to disappear into the darkness like a gory phantom. Was he a resident of Whitechapel? However, it is possible that he was seen by witnesses on at least one occasion. Nevertheless, the witnesses were not able to give police a specific description regarding the killer’s physical features. Due to the crowded conditions of Whitechapel and its dimly lit streets, alleys, and buildings, there were countless places to provide cover for a stealthy killer. If he lived in the area he would be familiar with the layout of various neighborhoods and could escape into the night undetected. Jack might also have been adept at gaining the confidence of his victims if he was familiar to them as as a customer or if he looked like—and conducted himself as—a resident of the area. On the other hand, Jack might have presented a glib, charming demeanor to his victims just long enough to put them at ease and cut their throats.

After 125 years, we cannot know what motivated Jack the Ripper to commit several vicious murders. Modern criminal profilers tend to conclude that a prominent sexual element was present in each killing. None of the victims were sexually assaulted as that term is usually defined today. However, the use of a knife may have had a sexual connotation. The killer would also need to be up close and within an arm’s length of the victims to commit the murders, making the act all the more personal. The act of crudely mutilating the women and then removing their wombs may also have been regarded by the killer as an act of extreme sexual violence. The victims’ bodies were found in positions as if the killer had put them on display, especially in the case of Mary Kelly. This could have been Jack’s way of objectifying his victims; trying to show them as less than human.

But human they were. In the lore, mystery and conjecture surrounding the subject of Jack the Ripper, people often lose sight of his victims. They were, as follows:

Polly Nichols; murdered August 31st, 1888.

Ann Chapman; murdered September 8th, 1888.

Elizabeth Stride; murdered September 30th, 1888.

Catherine Eddowes; murdered September 30th, 1888.

Mary Jane Kelly; murdered November 9th, 1888.

Stride and Eddowes were killed the same night, approximately 45 minutes to an hour apart. These killings are often referred to as the “double event.”

Jack the Ripper’s victims were certainly not model citizens. All five women were prostitutes and prone to drinking excessively. But they were not just victims of the world’s most infamous serial killer, they might also have been victimized by a life they could not easily escape. They are dead. But Jack the Ripper is still with us today. He has become a larger-than-life figure, immortalized in film, books, movies and plays even though his identity is still a mystery and no one knows what he looked like. “Ripper Tours” are popular in London. Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum, the most renowned of its kind, has no wax figure of Jack the Ripper in its Chamber of Horrors. He is depicted as a shadow, a fitting depiction of a predatory killer who stalked human beings and disappeared into the damp darkness of Whitechapel.

Photo courtesy of East London Historical Society