Crash Landing: The 1969 Seattle Pilots

| Published March 5, 2014 |

By Kevin Robbie

Thursday Review contributor

As the tumultuous decade of the 1960’s drew to a close, America had witnessed significant social upheaval and change resulting from the war in Vietnam, the Kennedy assassination, the civil rights movement and other events, including the zenith of the American space program. Against this backdrop of change and uncertainty, many people sought comfort in familiar activities and habits such as baseball.

Baseball is regarded as the major sport most rooted in tradition and the most prone to gradual, incremental change. During the early and mid-1960’s major league baseball had expanded to twenty teams from the original sixteen. In addition, the National League had returned to New York after the Dodgers and Giants moved to California and baseball’s western momentum had seen teams added in Los Angeles and Houston. The population of the western United States had grown and the interstate highway system had expanded as well. Baseball’s regular season had been increased to 162 games to reflect the greater number of teams. Otherwise, the structure and pace of the game remained largely intact and baseball was still the game which many fans had grown up enjoying.

By late 1967, the urge to expand had returned to the major leagues and was motivated, in part, by the potential legal ramifications of the move of the Kansas City Athletics to Oakland. The A’s owner, Charlie Finley, had moved the team after several seasons of futility and financial hardship in Missouri. Stuart Symington, an influential Missouri senator, threatened action in Congress to abolish baseball’s anti-trust exemption, which tied a player to an organization in the era before free agency.

Although voters approved a bond issue for a new stadium in Kansas City, Finley moved the team to Oakland, where construction of a new stadium was already underway. Senator Symington blasted Finley on the floor of the Senate and uttered his threat against the antitrust exemption. Major League Baseball responded by announcing another round of expansion, guaranteeing an American League franchise to Kansas City. American League owners selected Seattle as the second expansion franchise. The National League, not to be outdone, added Montreal and San Diego.

During the 1960’s the city of Seattle had enjoyed sustained economic growth—developing and maintain major defense contractors, avionics, and airplane manufacturing, to name but three—and the city hosted the World’s Fair in 1962. The fair turned a rare profit. The exposition left behind several cultural and sports venues, including the 605-foot Space Needle. One purpose of the fair was to provide a glimpse or gateway into the potential of the future in terms of lifestyle and technology.

Many Seattleites believed their city was ready to shed its provincial reputation. The world’s Fair was one method for doing so. Major league sports was seen as another avenue for civic pride and image-building. To that end, Seattle was awarded an NBA expansion franchise, the Supersonics, in 1966. The future appeared bright for the prospects of major league sports in Seattle.

Seattle had a rich history of minor league baseball, dating back to 1890. Seattle fielded a team, the Rainiers, in the Pacific Coast League (PCL) from 1919 to 1968. The team, in brief interludes, had also been nicknamed Indians and Angels. Seattle’s PCL team won seven league championships during those years and enjoyed impressive attendance from 1938 to 1952. They also won the league pennant in 1966. However, in the late 1950’s attendance at minor league games declined in general, due in part to increased television coverage of major league games.

Local brewery magnate Emil Sick purchased the team in 1938 and a stadium was built for the team. Sick’s popular “Rainier” beer was sold at the games which certainly did not hurt attendance at the new venue. The stadium was named “Sick’s’ Seattle Stadium” after the owner. The name “Sick’s” became highly appropriate by the time major league baseball arrived in 1969.

Seattle’s new major league team, the Pilots, was owned and operated by two brothers, Dewey and Max Soriano. The Soriano brothers were lifelong residents of Seattle and both of them had worked for the Pacific Coast League, Dewey serving as league president. The brothers had extensive experience in the business aspects of professional baseball but the Sorianos lacked one vital resource – money. Most of the money used to pay the expansion fee and to pay the team’s start-up costs was borrowed from a man named William Daley.

Dewey Soriano met William Daley in 1965. Daley was the former owner of the Cleveland Indians and had once considered moving that team to Seattle. He continued to believe that the city could be a viable market for major league baseball. The Sorianos asked Daley for a loan to pay the expansion fee and offered him a significant ownership stake in the franchise. He agreed and the Soriano brothers undertook to run the day-to-day operations of the team.

Although the fledgling franchise was initially greeted with enthusiasm it was beset with problems from the start and a dark cloud seemed to hover over it like the rain clouds prominent in the Seattle sky. The aforementioned stadium, Sicks, was at the center of the problems. The Pilots were handcuffed by an onerous lease which compelled team management to charge high ticket prices. Thus, fans paid major league ticket prices to attend games in a run-down minor league venue. Voters in Seattle and in King County had earlier approved a bond issue to construct a new, domed stadium which was supposed to open in 1972; an affirmative vote on the issue had been a prerequisite for major league approval of the franchise. In the meantime, the Seattle city government promised renovation of Sicks to bring it up to minimum major league standards, including an expansion in capacity to 25,000 fans.

The renovations began only in January, 1969, a mere three months before opening day. Work began in the midst of the worst Seattle winter in decades and the weather seemed a metaphor for the already frosty relations between team management and the city. City officials were determined to complete the work as cheaply as possible as cost overruns became apparent. As of opening day, seating capacity was only 17,000 and the stadium’s low water pressure was problematic all season and caused problems flushing the toilets. Most of the seats were either wooden benches or folding metal chairs and many of the seats had obstructed views of the playing field. In addition, the teams’ clubhouses were second-rate. The Pilots attendance reflected both the decrepit stadium and the team’s woeful on-field performance – Sicks failed to sell out even once in 1969 and saw only a few crowds in the 20,000 range.

Extensive renovations of Sicks weren’t made previously because the stadium was purchased by the city in 1965 in anticipation of the property being utilized for the new Thomson Expressway. Another problem was that baseball expansion was expected around 1971. When the planning was moved up to 1969, the issue of the condition of Seattle’s stadium became magnified. However, the city council and mayor were of the opinion that their responsibility was simply to furnish a stadium, not attract a baseball franchise. The mayor, Dorm Braman, never attended a Pilots game. Baseball was a low priority for the city government and the city frequently clashed with the main contractor responsible for stadium renovations.

As of opening day, April 11, part of the right-field fence was incomplete and some fans were watching the game, for free, through the gaps. The scoreboard installation was only completed the night before and carpenters were still installing wooden benches after the game was underway. Fans who had paid for reserve tickets ended up sitting wherever they could find a seat. The condition of the park and the huge delays in the renovations had created an atmosphere of animosity between team ownership and the city. The team claimed from day one that the city was unresponsive to complaints about the stadium and the city would accuse the team ownership of trying to renege on the lease.

Bill Sears, the Pilots public relations director, once related in an interview an example of the stadium’s issues in microcosm. He told of an incident when a drunken fan had become accidentally locked inside a portable toilet after falling asleep. Sears offered the story as symbolic of the Pilots’ season. He also stated that the condition of the stadium was a deterrent to fans attending games. The Pilots also had a very limited marketing and advertising budget. The team had secured a favorable radio contract but was unable to negotiate an equitable television deal. According to Sears, the local TV stations claimed the team’s owners wanted too much money. Also, the cost of the AT&T line was high enough that advertisers were leery of paying the fees for the broadcast lines. Thus, team revenues were to become more dependent on ticket sales. That’s a valid idea if the team performs well on the field.

The team won its inaugural opening game at home, 7-0 over the White Sox, after the Pilots had split two games with the Angels in Anaheim. As late as June 28th, the surprising Pilots were only six games out of the division lead. But then injuries hit, the team roster’s lack of depth caught up to it and the mediocre attendance dropped precipitously. The Pilots were a dismal 15-42 over July and August, including a 0-10 homestand. They finished the season with a ledger of 64-98, in sixth place, 33 games out of first.

In early September, the team’s creditors began to go public regarding money they were owed. Principal owner William Daley also went public and issued what amounted to an ultimatum – “Seattle has one more year to prove itself,” he stated to the press. Privately, he had already decided to not invest any more money into the sinking ship. His ploy with the media backfired as resentful fans continued to stay away. The issues regarding Sick’s stadium showed no sign of being solved soon and construction on the new stadium hadn’t even started. The dark clouds following the team all season had turned black.

At the conclusion of the season, Daley and the Soriano brothers decided that the only viable option was to sell the team. Initially they attempted to find a local group to keep the Pilots in Seattle. When several groups were found wanting for various reasons, the Sorianos filed bankruptcy. During the 1969 World Series, they agreed to sell the team to Milwaukee businessman Bud Selig (currently the Commissioner of Baseball) and the Seattle Pilots became the Milwaukee Brewers.

The Pilots are an obvious example of how not to operate a baseball franchise. They are the only team in the modern baseball era to move after its inaugural season. Ultimately, they were grounded by a series of blunders, bad decisions and misfortune. The owners were seriously over-leveraged, under-capitalized and could never catch up due to bad attendance and a roster in continual transition. The city failed to properly renovate Sick’s Stadium which led to a contentious relationship with Pilots ownership and motivated the fans to stay away. In addition, the team was never adequately marketed. Finally, Seattle had experienced an economic downturn in 1969 which combined with the high ticket prices to further impede attendance.

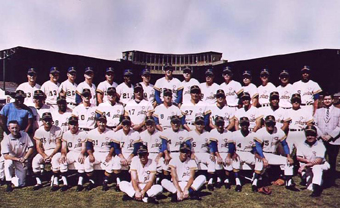

In spite of a legacy of mismanagement and shattered expectations, the Seattle Pilots retain an odd mystique. The ephemeral quality of the team is certainly a factor. Pilots uniforms and caps are popular with collectors. Many former players recall fond memories of their time in Pilot’s blue and gold. Jim Bouton’s book “Ball Four” has also contributed to the team’s legacy. Former Pilots outfielder Mike Hegan, recently deceased, once said “it’s like the Pilots have a cult following or something…” Outfielder Steve Whitaker once stated “We were the orphans of the league, the mutts.” Jim Gosger added “The Pilots were quite a collection of guys, very laid back and very likeable. There was no pressure because we knew the team wasn’t very good.”

1969 was the season on the fly for the Seattle Pilots. The ultimate reason for the demise of the Pilots was baseball’s rush to expand for the ’69 season. If the original plan for expansion in 1971 had held, the franchise might have begun its life on a more secure foundation. Assembled in slap-dash fashion to be ready in 1969, the Pilots were undermanned, underfunded and, perhaps, underappreciated.