Image courtesy of Capitol/EMI/Apple Records

A Splendid Time is Guaranteed for All:

Sgt. Pepper at 50

| published June 14, 2017 |

By Kevin Robbie and Alan Clanton,

Thursday Review contributors

June 2017 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the release of the Beatles’ landmark album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, arguably the first and most famous concept album in pop music, and by many accounts the best album in rock and roll history.

Sgt. Peppers was, by most lights, the high point of creativity for the Beatles, and a record widely considered the single most influential of the period. Over the decades, critics and readers of Rolling Stone magazine have ranked it number one among all rock and roll albums, including a 2003 ranking which placed it at number one among 500 most important rock albums. Furthermore, its innovative and dazzling cover art may make Sgt. Pepper’s the most famous album cover of all time—in any era or genre. Indeed, the legacy and cultural impact of the album continue to reverberate five decades after the album’s highly anticipated release.

But its backstory—as is fitting with many stories of the Beatles as a group—is complex, layered, and can be told fully only in the context of the times.

Just prior to Sgt. Pepper’s, Beatles fans had waited ten months for the group to release another album. Their previous work, Revolver, had topped the charts in August of 1966 and presaged a new and more experimental sound for the group. The release of Revolver also coincided with the Beatles’ decision to stop touring and become strictly a studio band.

There were various reasons behind the group’s decision to suspend touring, among them the fact that constant touring and stage appearances exhausted the band physically and took its toll mentally as well—a common problem for many rock bands. But in the Beatles’ case, the grueling pace of touring also inhibited musical experimentation and creativity—factors which they regarded as central to their musical growth and success. Beatles albums each displayed a distinct progression in the group’s sound and they were eager to continue the progression but they needed extensive studio time to do so, which was no longer possible given the burdens imposed by live performances. Besides, members of the group—especially John and George—had come to the inescapable conclusion that their live appearances had become little more than pantomime, as the screaming and shrieking of the live audience essentially made it impossible for anyone to hear, performers or fans.

With the end of touring, the Beatles also decided to take vacations and take stock in themselves and their future. John took a small role in the satirical antiwar movie How I Won the War, a film directed by Dick Lester, the man behind A Hard Day’s Night. Otherwise, he went out at night or stayed home watching TV. Paul was spending time with his girlfriend, Jane Asher, and accompanying her to concerts, plays and art galleries. Paul also took vacations to France and Kenya. George was beginning to immerse himself in Indian music and religion and he began lessons on the sitar, the early stages of his lifelong interest in Eastern philosophy, culture and music. Ringo was spending time with his kids and indulging his new hobby of photography.

However, music was always a presence, and was never far away from the mindset of all four Beatles. The year 1966 was a seminal moment in rock history. The spring had seen the release of the Pet Sounds LP by the Beach Boys, the single “Eight Miles High” by the Byrds, the LP Aftermath by the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. Taken individually, any one of these musical milestones could be viewed as pivotal; taken as a whole, they were a harbinger of experimentation and radical change. In addition, Jimi Hendrix first arrived in London with his new manager, former Animals bassist, Chas Chandler. The new supergroup Cream first performed live in July, in Windsor—a band made up of Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton. The music being created by these acts was, along with the Beatles, pushing the boundaries of popular music forward at dizzying speed. New, exciting sounds were being heard on a nearly daily basis on radios and record players around the world, much of the new music spurred by the enormous success of the Beatles.

Furthermore, 1966 was the year in which the “album” or LP, which is to say recordings made to be played at 33 1/3 rpm on a turntable, outsold 45 rpm record within the broad category of pop music. Prior to 1966, pop music fans—rock and roll, country, jazz, soul, blues (pretty much any category except musical and classical, for obvious reasons)—just bought “songs” as packaged in the form of a 45 rpm record. There was the one song, and there was whatever the record company slapped onto the reverse side. For rock and roll, this hinge moment in which the long-play album overtook the 45 would prove to be important, especially for those writers and performers on the cutting edge of innovation.

Still, an unanswered question lingered over the music landscape like a resonant guitar chord: what were the Beatles up to? By autumn of 1966, it appeared to their fans that the Beatles had gone into hibernation. They had not released an album since August, and it had become obvious to those in the music press that the group had stopped touring. Though no public announcement had yet been made regarding live performances, the absence of any news simply made it much more suspenseful to Beatles fans worldwide.

Though they had not seen or heard from each other much during the late summer and early autumn of 1966, the long hiatus spent apart had not dampened the creativity of each Beatle. Individually, they had continued writing songs, and as always, they were receptive to musical trends appearing around them. In spite of their hard-earned free time and vacations, the four Beatles realized that it was in the recording studio where they truly thrived. Creativity seeks an outlet, so the group returned to Abbey Road Studio #2 on November 24, 1966.

While in Spain filming How I Won the War, John spent much of his free time on the beach with an old acoustic guitar, and where he was often in a reflective and introspective mood. His most famous song from this period reflects his state of mind at the time.

“Strawberry Fields Forever” quickly became one of the group’s most iconic songs. It was released as a double-A side with Paul’s own nostalgic classic, “Penny Lane.” Both songs evoked memories of John and Paul’s Liverpool childhoods. The original idea was to include both songs on the new, upcoming album, which the Beatles were to begin recording in February. However, Capitol Records and EMI, the Beatles’ British label (and the corporate owner of Capitol) were pressing Beatles manager Brain Epstein and producer George Martin for a new single. The two songs were released as a single—a 45 rpm record—on February 17, 1967.

“Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” represented another progression in the Beatles sound, following the album Revolver and the single of “Paperback Writer” and “Rain,” which is considered to be the first psychedelic single, from 1966. The group’s retirement from touring and time spent on personal activities had brought them full-circle in terms of musical inspiration. John and Paul independently came up with the two new songs based on images and memories from their childhood in Liverpool. “Penny Lane” eventually reached number 1 in the charts, but “Strawberry Fields Forever” climbed to the number 2 spot. Because the record was considered a double-A side, the record broke the group’s string of twelve consecutive number 1 singles. This chart position was determined by an anomaly in the mathematics of pop charts—the two sides were counted separately in terms of sales and air-play. In short, one side cancelled out the other.

Meanwhile, the Beatles resumed their work in EMI studio 2, Abbey Road, in January, before the “Strawberry Fields”/“Penny Lane” single was released. For the first time, EMI placed no restrictions on their studio time and, of course—now that the news was official that live performances were off the agenda—there was no tour looming and no intense pressure on the calendar.

But there was pressure in other ways. Though the Beatles originally intended for “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” to appear on the upcoming album, Epstein and Martin decided, partly because of lobbying from the execs at EMI, to leave those songs off the new full-length record. Thus, they were released the two songs as a single in February, 1967, to widespread critical and popular acclaim. The songs also proved to be a harbinger of things to come.

Before the release of the new single, the group returned to the studio to begin work on their next LP. Paul, during a vacation, had come up with the idea of the Beatles recording the new album with the mindset of having alter egos in the studio. He envisioned a hybrid psychedelic/Victorian band wearing bright, shiny uniforms, performing new music at a small-town band-shell. Victorian and Edwardian military-style clothing and bric-a-brac were popular in the 1960’s, and Paul’s tastes were always influenced by his father’s music-hall experiences as a musician in the 1930’s. Those stylings, trappings and cultural factors were to become notable elements on the finished LP, and would shape the unique direction the album would take.

The goal—as envisioned by Paul and relayed to the other Beatles—was to create an album which, in a sense, would tour for the group in its stead. The songs would be “performed” by the fictitious band, and every song would be related to the band, just as every song would be part of the larger musical tableau. The eventual package concept would come to be known as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The other Beatles were immediately open to Paul’s concept, and were relieved as well that Paul also had no desire to return to touring and live performance—especially since it was clear from the start that Sgt. Pepper’s would require a commitment to spending time in the studio. After a few months of rarely seeing each other, Paul and John resumed their songwriting side by side, often visiting each other’s houses and scribbling ideas in old notebooks, often hammering out tunes on a battered old piano and an acoustic guitar. They ultimately took those basic tunes and lyrics and transformed them—with George Martin’s help—into the sounds of Sgt. Pepper.

Early into the process, Martin and the Beatles became keenly aware that the songs of the new LP would require the use of recording techniques and studio technologies never used before. Martin enlisted the help of Geoff Emerick, a 21 year old EMI studio engineer. Emerick had worked with Martin and the Beatles on the Revolver LP and he had assisted with the artist’s test for the Hollies. During the “Revolver” sessions it was Emerick’s clever idea to record John Lennon’s voice through a Leslie speaker to achieve the effect of chanting monks on the track “Tomorrow Never Knows.” His talent would be put to good effect on Sgt. Pepper.

The Sgt. Pepper's LP, the Beatles eighth studio album, consists of thirteen tracks covering nearly forty minutes of more-or-less seamless sound. This was accomplished through the songwriting narrative and the musical arrangement, but also through other means as well. For one, they decided to eliminate vinyl “banding,” the momentary gap traditionally, and deliberately, left between tracks; instead, each song would end by bumping headlong into the next, with little or no buffer, and thus giving the impression of the album as a continuous performance by Sgt. Pepper’s band. Far from jarring (as some might have predicted), the effect is in fact just one of many tools meant to tie the album’s songs into a well-crafted, cohesive whole. This device was one of only many innovations on the album, and one which would later be successfully copied by groups ranging style from Led Zeppelin to Boston, from Queen to Green Day.

Another important innovation was known as automatic double-tracking, or ADT. Ken Townsend invented ADT during the Revolver sessions. ADT was an analogue recording technique which simultaneously double-captures sounds so as to avoid separate multi-tracking, especially of voices. John, in particular, didn’t like the extra effort and time required to overdub his voice in second recording sessions, third sessions, fourth, and so on. Besides, the whole business of going back into the booth to record a song again and again was painstaking and prone to mishaps, not to mention time consuming. The ADT process solved the problem.

In addition, Martin, Emerick and Townsend devised or improvised a dozen other technological solutions to some of the sounds and effects sought after by the Beatles, especially John and Paul. Among the new techniques employed: signal processing, a method by which music or voice or sound effects—individually or as a whole—can be modified, bent, reshaped or enhanced to exacting standards. As it had done with Brian Wilson in the studio with the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, this gave the Beatles almost unlimited space with which to experiment with music, voice and sound—an open field of innovation onto which all four members of the group ran with abandon.

Other technological advances found their way into Sgt. Pepper’s. Among them, something then known as varispeeding—a technique relatively new at the time, but one which allowed the musicians and engineers to speed up or slow down certain sounds, voices, instruments. The effect was used most notably on “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” where some vocals and sounds have been intentionally “thickened” or “thinned.”

Unusual instruments and improvised sounds were employed, as well. On “Lovely Rita,” George and John blew through combs into which strips of paper had been inserted. “Fixing A Hole” featured producer George Martin on the harpsichord. A series of calliopes can be heard on “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite,” which closed Side One of the album. To achieve the “hurdy-gurdy” circus effect desired by John on “Mr. Kite,” Martin and Emerick spent hours cutting up audio tapes of calliope music, tossing the cut-up strips onto the floor, and reassembling and re-splicing the bits of tape randomly, even backwards. For George’s Indian opus, “Within You, Without You,” a small orchestra composed of Indian musicians was hired to play using eastern instruments, including sitar, tambura and tabla.

Aside from a variety of unusual or improvised percussion effects, among them the eastern instruments, the Beatles, working with Martin and Emerick, also decided to place microphones much closer to Ringo’s drum than what would be the typical distance between mic and drum or cymbal. To compensate for the extreme proximity, damping was employed. As on Revolver, George again expanded his guitar virtuosity as well as his experimentation with other string instruments, in this case the use of the tambura.

“When I’m Sixty-Four,” a light jazz ditty sung by Paul, includes the use of a bass clarinet and two B-flat clarinets, along with tubular bells layered in amongst the electric guitars. Paul, who wanted the voice of the singer to evoke youthfulness as well as ruefulness, worked with Martin and Emerick to alter the song’s key from D-flat to C-major (raising it one semitone) in order to add sparkle and boyishness to the vocals.

“Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” may be the most famous song believed to be about psychotropic drugs ever written. Its dreamlike lyrics reflect the culture of experimentation with LSD prevalent at the time, with vivid but hallucinatory images woven together in a seamless, fluid journey. “Picture yourself in a boat on a river / with tangerine trees and marmalade skies / somebody calls you / you answer quite slowly / a girl with kaleidoscope eyes.”

Likewise, the complex medley “A Day in the Life” also draws the listener into a dreamlike state of non-sequiturs and diary-like hallucinations, as well as an ironic take on “the news” and the fickleness of “the crowd.”

At the end, Sgt. Pepper's featured perhaps the most famous closing to any LP, the last, thunderous chord of “A Day in the Life.” Following a long, tense orchestral crescendo, three pianos and a harmonium were struck to produce a booming E-major chord, a VI to the song’s tonic G-major. The recording level was so high that a squeaking chair is audible in the background. “A Day in the Life” required 34 hours of studio time to record. The Beatles second album, Please Please Me required only 12 hours for the entire LP.

Another fact about the recording of Sgt. Pepper is that the album was mixed in mono because very few people in 1967 had stereo record players—true stereo was still somewhat costly strictly for hi-fi aficionados—and to prove the point, none of the Beatles attended the sessions for the subsequent stereo mixes. Indeed, on certain versions of vinyl and even CD pressings, if you listen with the balance turned to just one speaker, you hear Sgt. Pepper's like you've never heard it before, missing backing vocals, no drums and guitars missing from the mix.

According to George Martin, the Beatles also wanted to craft a form of musical and aural diversity never before heard in rock music.

“The Beatles insisted that everything be different,” Martin wrote later, “so everything was either distorted, limited, heavily compressed, or treated with excessive equalization. We had microphones right down in the bells of the brass instruments, and headphones turned into microphones attached to violins.”

Music historians often point out the lasting impact of Sgt. Pepper’s on both studio technique and music production and engineering. To explain to John the Automatic Double Tracking (ADT) developed by Townsend, George Martin jokingly—and in typical Beatle style—as described the system in nonsense terms. “Your voice has been treated with a double-vibrocated sploshing flange…it doubles your voice!” Though John and the others immediately realized Martin was joshing, John thereafter referred to the process as “flanging,” a term soon adopted by the wider music industry and used for decades afterwards.

Though recorded in mono, the extensive and complex use of so many layers of technique and effect and innovation created what some music historians describe as a “three-dimensional sound”—a distinct and dramatic break with the “flat” or linear sound previously found in most pop and rock music. That 3D approach to the studio influenced the scores of bands that were following closely along the path forged by the Beatles, and contributed mightily to the overall quality of later albums by groups as diverse as The Who and Yes, Boston and Talking Heads, Paul Simon and Dire Straits.

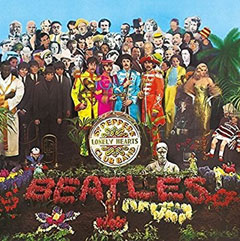

Sgt. Pepper’s impact was not limited to its music. With its front cover art—arguably the most famous album design in rock history—and its inner sleeve, the album can be seen as a self-contained piece of audio/visual art. Sgt. Pepper's is full of vibrant colors, evoking the bright colors and designs prominent in the psychedelic era, the tones and intensity of the colors matching those evoked by the rich, layered music. On the front, the Beatles are depicted as Sgt. Pepper’s band, decked out in Victorian-style uniforms designed by a Dutch design group known as The Fool. The group posed with marching band interments in front of a group of people who, one may infer, are present to attend a concert by the band. Alongside the Beatles in their Sgt. Pepper’s uniforms are four wax figures of an earlier incarnation of the Beatles, full sized replicas of the Fab Four borrowed from a London museum.

Carefully arranged and visually choreographed for weeks by artist Peter Blake in a studio, and photographed by Robert Fraser, the collage is constructed of life-sized cardboard figures arranged in tiered layers to convey an almost three-dimensional effect—perhaps the most visually complex album cover ever created, and complete with elaborate floral arrangements, brass instruments, a palm tree, a small TV set, and dolls and figurines of various sizes. Blake had asked all the Beatles to contribute by naming some famous people whose images they might want included, a process which later so worried the more risk-averse Beatles manager Brian Epstein that Epstein insisted letters be sent to every living person depicted on the cover. Most celebrities agreed, including (eventually) a mildly irritated Mae West who asked “what would I be doing in a lonely heart’s club?”

Among the scores of faces seen among the cut-out figures: early film comics Laurel and Hardy, writer Edgar Allan Poe, actor Tyone Power, Olympian swimmer Johnny Weismuller, illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, actor Marlon Brando, and guru Sri Lahiri Mahasaya. Also in the image are the wax figures of boxer Sonny Liston and actress Diana Dors, and the cutout figure of comedian Issy Bonn, whose large hand appears directly over Paul’s head.

Ironies and sardonic jokes abound. Though carefully composed and arranged to make the overall cover image appear to be a joyful and party-like musical gathering of famous people, the wax figures give a vibe more akin to a funeral service—all the more noticeable when one includes the visuals formed by the floral arrangements on the ground amidst freshly tilled earth. The addition of the little television set—juxtaposed near dolls, figurines, and statuary (two of them depictions of Shirley Temple)—adds a modern element to the Victorian mosaic, but also injects a Marshall McLuhan-esque observation…the banal image of the TV on the same plane as Lewis Carroll, Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw. A hookah tobacco water pipe sits just inches from a tuba. Two wax figures—hairdresser or dressmakers dummies—appear as anonymous, partially obscured female faces within the whimsical crowd of the famous and infamous.

The Sgt. Pepper’s cover may be the most famous imaginary party guest list ever created. Mae West appears next to Lenny Bruce; W.C. Fields next to Carl Jung; Oliver Hardy next to Karl Marx. The face of early Beatle Stu Sutcliffe—who died of an aneurism—can be seen just above that of Sonny Liston. Actress Marilyn Monroe appears to be conversing with writer William S. Burroughs.

In front of the group and the crowd of celebrities appears a flower bed—or an arrangement of floral items freshly planted in newly turned dirt—with an assortment of stone objects and figurines partially embedded within it. Some of the flowers spell word “Beatles.” Dolls and statuary reflect the diverse styles of Japan, India, Mexico, India and England. One of the Shirley Temple dolls—embraced within the lap of an even older “grandmother doll”—wears a striped sweater with the words “Welcome Rolling Stones: Good Guys.”

Debate has existed for years as to the real purpose of the crowd’s presence as well as the flower bed and even the bass drum immediately in front of the four Beatles. Those debates gathered more rule in 1969 when the first “Paul is dead” rumors began surfacing. Fans began examining the elaborate album cover (front and back) as well the music, for any “clues” they could discover. The trail of “clues” in that urban legend began with Sgt. Pepper’s, and its hundreds of tiny details.

Even the back-cover of Sgt. Pepper’s became prominent and game-changing. Sgt. Pepper’s was the first album to show a complete list not just of song titles, but all of the songs’ lyrics as well. The lyrics are printed in black and displayed on a bright red background, along with another, smaller photo of the band. In addition, the album provides a third photo of the Beatles printed on the inner gatefold, showing the band sitting in front of a bright yellow backdrop (also photographed by Fraser). Inside the jacket, packed beside the disc itself, was a sheet of Sgt. Pepper cutouts printed on heavy, coated paper. The cutouts even included a Sgt. Pepper mustache.

Critical reception of the album was generally good. Among its notable achievements, it became the first rock album to be nominated and win for Album of the Year at the Grammy’s—a turning point in which rock and roll music clearly and definitively became the dominant factor in both record sales as well as critical interest. The landmark album also grabbed Grammy’s for Best Album Cover, Best Engineering, and Best Graphic Arts. The year it was released, Newsweek critic Jack Kroll described Sgt. Pepper’s as a masterpiece on the same par with the ironic and modern works of T.S. Eliot and Harold Pinter. Furthermore, many critics in later years cited Sgt. Pepper’s for permanently integrating the cover art and sleeve materials into the overall creative and commercial aspect of the album; never again would a record cover and its thin paper sleeve serve as merely a vessel for holding music. Other critics—art critics as well as music critics—have suggested that Sgt. Pepper’s is the best and most shining example of Pop Art ever conceived.

The album spent a then-unprecedented 27 weeks at number one on the British music charts in 1967-68, and some 15 weeks at number one in the United States. Sgt. Pepper’s also climbed to number one on the charts in Sweden, Canada, Norway, West Germany, Belgium, New Zealand and Australia. It remains one of the biggest selling records in rock history.

A note from Kevin Robbie: as an avid Beatles fan myself, one of the earliest memories I have is listening to Sgt. Pepper’s with my older brother and his friends. We also took a family trip to New England in the summer of 1967 and music from Pepper—I especially remember “A Day in the Life”—was prominent on virtually every music station we could find on the dial. Even after fifty years, those memories are still vivid for me and I am sure will always be with me. They remind me of happy times and hearing the music of the Beatles never fails to put me in a good mood. Perhaps that is the true legacy of the Beatles music and Sgt. Pepper specifically. It guarantees us a splendid time.

Related Thursday Review articles:

George Martin & The Beatles First Record; Kevin Robbie; Thursday Review; March 18, 2016.

Brian Epstein, George Martin, and the Early Beatles; Kevin Robbie; Thursday Review; January 5, 2015.