Republican National Convention 2012 in Tampa/photo by Alan Clanton

Kasich’s Ohio Victory &

the “Brokered Convention”

| published March 17, 2016 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

For the Republican Party, the jury is still out on Donald Trump. It’s ironic, really.

By all rights and by most definitions, the billionaire is the front-runner for the GOP nomination, and his four solid Mega Tuesday wins, alongside a squeaker win in Missouri, seem to have him on a winning trajectory to the Republican convention in Cleveland. Historically, Republicans like early front-runners, and applaud any primary and caucus season that reaches an early conclusion. Less fuss, less mess, and everybody rally around the winner…that sort of thing.

But neither Ted Cruz nor John Kasich got that memo late Tuesday night, nor had they received it by Wednesday morning as the dust settled. And the so-called Republican “establishment” has not conceded that Trump is their party’s de facto winner, nor have the party elders felt compelled to bend the GOP’s agenda to fit Trump’s talking points, which many conservatives say is at odds with the party’s traditions.

Trump won big on Tuesday in Illinois, North Carolina, and Florida, where he demolished what was left of Florida Senator Marco Rubio’s firewall, forcing the junior Senator—once the darling of the GOP’s mainstream and establishment figures—to suspend his campaign altogether. Trump won in the Sunshine State by 46%, and walked away with all of Florida’s 99 delegates, adding to his already impressive trove of 673 total delegates. Trump also won big in Illinois and in North Carolina, beating back challenges in each state from Texas Senator Ted Cruz.

In short, Donald Trump should be—by any reasonable measure—on the easy highway to the nomination, cruise control set to 70, the radio blaring his favorite opera tunes.

But the fight within the GOP is apparently far from over. Despite Rubio’s flameout in sunny Florida, and in spite of Trump’s string of big wins, the Republican Party is still engaged in a bitter civil war for control of its 2016 narrative and its future. Trump may have won solid, even slam-dunk victories in several big states on Tuesday, but the party elders are now talking even more feverishly of a contested convention in Cleveland. John Kasich’s win in Ohio—a winner-take-all delegate state—hands Kasich 66 delegates and deprives Trump of some of the running room he badly needed to pull away from his competitors, especially Ted Cruz.

According to the smart math people—that is to say the sort of people paid a lot more than the folks here at Thursday Review to study the metrics of such complex things—because Trump lost in Ohio, the billionaire must now win no less than 60% of all remaining delegates if he wants to have any hope of entering the convention this summer with enough momentum to win on the first round of balloting. Under RNC rules, if he does not muster the required 1,237 delegates to win, the issue is turned back over to all the qualified delegates and party leaders assembled in the room in Cleveland to decide.

This, dear readers, is what is known as a contested, or “open,” convention. Advocates of the open convention prefer that moniker because it exudes a sort of big tent form of democracy, with folks wandering the convention center caucus-style bargaining over votes and comparing health care plans and foreign policy talking points. There are negotiations and deals, names are floated, more votes are taken. There are cigars, colorful shirts and funny hats, balloons, hot dogs for the kids. Sounds like fun—democracy in action, right.

Except that the last time the GOP had an “open” convention, in 1964 in the Cow Palace in San Francisco, it tore itself asunder in an epic showdown between moderates and conservatives, a fever-induced brawl in which the insurgents and whippersnappers aligned to Barry Goldwater fought the silk suits and party regulars led by New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Televised live with commercial breaks for soap, laundry detergent and refrigerators, that convention was not a pretty sight. In fact, it got ugly. So ugly that sitting President Lyndon Johnson ran away with things in the fall, handing Goldwater a stunning defeat so famous that it was interpreted at the time as the beginning of the end of the Republican Party, and the funeral pyre of conservatism, then in its mainstream infancy.

That November 1964 loss was so devastating that the GOP basically made it a rule never to put on that kind of spectacle again. All Republican nominees become the de facto nominee no later than about mid-March (yesterday, according to my calendar), and only once since then has there been any genuine drama after late April, when challenger Ronald Reagan handed President Gerald Ford a string of defeats in several states, setting in motion a fight which lasted right up to the doors of the convention—but not inside, and not on live TV.

Especially after the Democratic convention of 1968, when riots surged just outside the convention hall in Chicago, the Republican Party became risk-averse. Conventions became a formality, and a made-for-TV opportunity to deliver the message, set the tone, and show unity. It has been thus ever since, and neither party—Democrat or Republican—has had an “open” or contested convention since 1968.

But Ohio Governor John Kasich—immensely popular in the Buckeye State and able to tap into a deep reservoir of goodwill—may have changed all that on Tuesday with his big win in Ohio. Granted, it was his home state, after all. But, as we also saw on Tuesday, the home field advantage doesn’t amount to much in the Year of Trump. The hapless Rubio was crushed under the weight of the Trump tide, losing to the billionaire 46% to 27%, carrying scant few counties in a state which he practically owned until a month ago.

Yes, Rubio, the guy that pummeled Charlie Crist so badly that Crist bolted the party. Yes, the same Rubio who was once the charmed protégé of Governor Jeb Bush. The same Rubio which the Hillary Clinton strategists once said in a top secret internal memo would cause them the most grief and worst headaches in a general election. Yes, that Marco Rubio.

Kasich’s win in Ohio catapults the Governor into the driver’s seat for the establishment, which is to say the Anti-Trump movement. It’s not clear that he should be honored to occupy that chair. Previous holders of the title are etched on a long list of the recently departed: Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, Rick Perry, Scott Walker (ah, the good old days of Scott Walker). Other anti-Trumps rose and fell: Carly Fiorina, Dr. Ben Carson, Rand Paul. Indeed, Ted Cruz says openly that nothing that Kasich has done up to this point makes him deserving of being the Republican nominee—and winning his home state of Ohio should not be considered some crowning achievement.

“It is mathematically impossible,” Cruz told CNN a few days ago, “for John Kasich to become the nominee. At this point, he had lost 20 states before Ohio.”

Some would argue that Cruz has a point. As the only candidate who can rightfully say he has kicked Trump’s butt in multiple states—nine so far—Cruz ought to be the guy the party regulars turn to as if by a magnetic force. But that isn’t happening, at least not as swiftly as Cruz would like. Last week, he picked up the support of former candidate and former HP CEO Carly Fiorina, just days after he received the endorsement of the conservative magazine National Review. This week he picked the endorsement of Nikki Haley, the popular South Carolina Governor who had previously backed Rubio. But beyond that, Ted Cruz is still the least liked Republican in Congress, for reasons to complex and baroque to go into here.

Cruz and his supporters say “get over it.” Cruz may not be loved by his Senate colleagues, but Cruz also doesn’t particularly seem stung by the fact that he never won a Washington popularity contest. This is not about who gets invited to the best D.C. parties, or gets to play gold with President Obama. Cruz says it is about deciding who can best channel the anger and frustration of the GOP electorate into a winning strategy in November: Trump, who panders to the worst instincts of some voters, or Cruz, a consistent and reliable conservative with just enough inside-the-Beltway knowledge to get a few things done right the first time. He points to that National Review endorsement as more evidence: the magazine made a pragmatic decision by not backing Rubio, whose campaign was already operating on fumes, and instead backing Cruz—the one guy has has proven he can knock Trump off his stride.

And Cruz points to his wins in those seven diverse states as evidence that he alone can topple the Goliath named Donald Trump, and he says he can do it fair and square, long before the convention doors open. Meaning there is no need to talk about wild scenarios involving brokered conventions and stunt casting decisions—motions from the floor, for example, to nominate Paul Ryan or Mitt Romney or Newt Gingrich or Condoleezza Rice, all of which have been floated as possible ideas.

Here’s the short version: if Trump arrives in Cleveland with at least 1,237 delegates confirmed and in his corner, he wins on the first ballot. Game over. Republicans can either deal with it, or wander into the wilderness to form a third party, or—as has been suggested—a “temporary” party to serve as a shelter for anti-Trump Republicans.

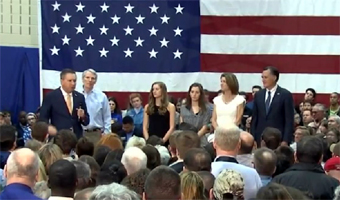

John Kasich campaigning with Mitt Romney in Ohio/

image courtesy C-Span

But if Trump arrives to the convention doors with less than 1,237, all bets are off. A failure by Trump to claim the nomination outright on the first round of balloting opens up the convention to more voting—and under the complex rules, increasingly large numbers of delegates are freed to vote as they choose with each passing go-round. This presents opportunities to either Cruz or Kasich to muscle-in on the loyalty of delegates once committed to Trump. But the door also swings both ways, as some delegates pledged to others can jump on Trump’s bandwagon—though that seems less likely. A so-called open convention also means more names can be floated. Enter the strange possibility that a candidate from earlier in the primary season sees their name tossed onto the floor for consideration: Bush, Rubio, Carson. Anything becomes possible, including a blast from the past: Romney, John McCain, Sarah Palin, Paul Ryan, Mike Huckabee.

Then there are the so-called nuclear scenarios. The RNC playbook has the provision for delegates, once all or most have been officially allotted and /or committed, to make minor or major changes to the convention proceedings and floor rules a couple of weeks prior to the convention coming to order. This is standard stuff, designed mostly as a formality and to allow a forum for scripting and arranging. Romney and others have suggested using that option to its full effect, rewriting the rules—in effect—to freeze out Trump, or at least blunt his impact upon entering the room. All of this would take place in plain view, and would obviously work best if Trump does not reach the magic number of 1,237 by mid-July.

Ben Ginsburg, a top Republican lawyer who has served as counsel to some past GOP candidacies says the next weeks and months could get messy as the intrigue and the legal wrangling heats up over delegate counts and delegate loyalty. Ginsburg predicts a variety of legal challenges as we get closer to the convention, including challenges to the RNC’s own rules and guidelines. Even at the convention, there could be complex parliamentary challenges to delegate credentials and delegate distribution.

Trump has already intimated as much in several speeches, in which he has called the 1,237 needed to nominate “arbitrary” and “random.” The RNC says the numbers are there for anyone to see, was agreed upon long ago in pre-planning sessions, and merely reflects the appropriate minimum hurdle to become the GOP nominee.

But at this point, Trump says that he deserves to be the nominee no matter what, and he points to all those angry voters in all those states who have backed him thus far in his insurgent campaign against the establishment. Cruz, too, thinks that any plan involving brokering or bargaining at the convention stinks, and reeks of backroom politics. Cruz is convinced he can win this on the level, as it were, if only all the people who don’t trust Trump decide to trust Ted instead.

On Wednesday, Trump went further, intoning that any attempt to deny him the nomination through parliamentary maneuver, trickery or legal shenanigan would trigger outrage, even violence.

“I think you’d have riots. I think you would have riots,” Trump declared on CNN, “I’m representing a tremendous many, many millions of people.” A top Trump spokesperson, Scottie Neil Hughes, said much the same thing later the same day, telling Wolf Blitzer that “riots aren’t such a bad thing,” and explaining that voters are angry and frustrated and ready for open revolt.

Kasich makes no particular secret that the key to his eventual success can only be found in a contested convention. His top strategists admit that his best plan is to keep plugging away, gathering positive review and attracting media chatter, and choosing his targets carefully, especially in states where he stands good chance of pulling off an upset—Pennsylvania, Maryland, then, elsewhere in the Midwest and Far West. All he needs to do, they say, is win two to three more meaningful contests to remain not merely relevant, but perhaps the best option for the party regulars and traditionalists who yearn for a Reagan-like leader. A few of the states in his sights are less Trump-friendly, and more open to Kasich’s message of inclusion, especially California, where some polls show Trump’s negative numbers exceed his positives.

With Rubio’s campaign suspended, Kasich also hopes to start a chain-reaction of endorsements and fundraising. With enough cash, he can soldier forward indefinitely, and he may benefit from the anti-Trump forces in their independent spending in select states. Romney and others have already been backing Kasich, and the governor plans more campaign appearances alongside Arnold Schwarzenegger. A California victory would be the ultimate prize for Kasich. Coupled with Ohio and at least one or two other states (his people suggest Connecticut and Wisconsin are ripe for a Kasich win), the Golden State would put him in a very strong position to maintain credibility if Trump has a flameout on the first ballot.

Besides, Kasich is the last man standing in a brutal war of attrition among the party regulars and establishment types, and especially among those in the GOP who favor inclusion rather than exclusion. It is that central reason, his team suggests, that Kasich performs better in some polls when matched against Hillary Clinton.

Meanwhile, the what-ifs are flying around like drones at a technology show. If only Rubio had been able to take Florida and its 99 delegates, the math experts point out, Trump’s challenge would be almost insurmountable, required him to win some 68.5% of all remaining delegates. If only the establishment could have punctured Trump’s great dirigible before New Hampshire, right after Cruz defeated the billionaire in Iowa, Trump may have crashed to the ground long before South Carolina. If only Jeb Bush had put on the brass knuckles and knocked Trump’s lights out (figuratively, not literally!) in the first or second debate last summer, Trump may not have been a factor at all.

Then again, the math experts like to point out, in a field crowded with at least 17 major candidates months before the first contest, anything can—and very likely will—happen. Even a contested political convention, something not seen since before most Americans were born.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Mega Tuesday Nudges Clinton, Trump Closer to Nominations; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; March 16, 2016.

Mitt Romney Offers Blistering Repudiation of Trump; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; March 3, 2016.