Image courtesy Tonight Show with Johnny Carson/NBC

Jazz Clarinetist Pete Fountain

Dies at Age 86

| published August 12, 2016 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

Jazz clarinet player Pete Fountain died this week at age 86 after a lifetime of performing his beloved and spirited jazz sounds.

Fountain’s legacy and impact is nothing less than transformative: some music critics credit him with popularizing the New Orleans brand of street and nightclub jazz, bringing it to mainstream audiences through his frequent appearances on popular television venues such as the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Indeed, without Fountain’s influence, the brand of New Orleans jazz—often commonly referred to as Dixieland—for which Fountain was a practitioner might have remained largely obscure to most Americans.

Fountain died of heart failure according to his manager and family spokesperson, son-in-law Benny Harrell.

Pete Fountain’s biggest inroads with Middle America—and arguably his most intriguing device for bringing his love of the lively New Orleans sound to a more sedate audience—were his frequent appearances on the Lawrence Welk Show, a program of so-called “champagne music.” Fountain was hardly an advocate of Welk’s lowkey and unthreatening mix of easy-listening tunes and performers; still, his frequent appearances were so popular with Welk’s huge audiences that he soon became a staple of the show’s line-up, and one of Welk’s most famous performers.

Born in New Orleans in 1930—his real name was Pierre Dewey Louis LaFontaine—Fountain was nudged toward wind instruments as a child when his family physician—almost out of desperation—suggested the young Pete take-up a woodwind or brass instrument as a way to improve his asthmatic lungs and labored breathing. Pete did exactly that, learning and practicing with a dozen wind instruments, but settling on the clarinet as his favorite. He was, as they say, a natural: his self-taught skills became so proficient that he was playing in nightclubs and bars alongside much older performers by the time his was in his early and middle teens. And by the time he was a senior in high school, he was so good he was already earning $125 or more per week, big bucks for a kid in World War II-era New Orleans. He was also already moving up the musical ladder, performing in some of the most elite nightclubs and music venues on Bourbon Street.

In 1950 he joined with trumpet player George Girard to form the Basin Street Six, a band which brought Fountain even more attention while also giving him a chance to continue to sharpen his skills on the clarinet. After a brief stint with the Dukes of Dixieland, Fountain teamed up with Al Hirt in 1954. Though he travelled occasionally and even lived briefly in Chicago and Los Angeles, Fountain always preferred his hometown of New Orleans.

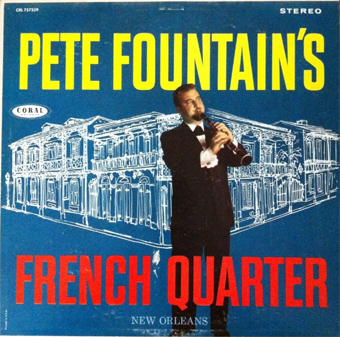

Image courtesy Coral Records

He recorded scores of albums over the decades, many of them loaded with what some critics derisively considered cross-over—a hybrid of easy-listening instrumental sounds and traditional middle-of-the-road jazz. He also recorded albums in a variety of specialized sounds, many of them concentrating on Dixieland, his speciality. His records sold by the tens of thousands, and eventually into the hundreds of thousands, and even those critics who gave him poor or moderate reviews of his own recordings praised him for his influence in elevating the New Orleans and Dixieland sounds out of obscurity and squarely into the mainstream and pop culture.

A television talent scout spotted Fountain during a performance at the Pier 600 in New Orleans, and immediately offered him an appearance on the Lawrence Welk Show. Though Fountain’s upbeat and edgy New Orleans style for all critical purposes clashed with Welk’s usual milquetoast routines of big band, polka and pop, Fountain was an enormous hit with viewers, and he became a regular on the show. Later, frequent appearances on programs like the Tonight Show and Merv Griffin raised his status even more.

In 1960 he opened the first of several nightclubs he would operate in New Orleans, business and musical ventures he would maintain throughout his life. In the 1960s his club and restaurant, the French Quarter Inn, was so popular that A-list singers, musicians and movie stars routinely made the trek to his club just to see Fountain and his other band members—including Oliver “Sticks” Felix and Paul Guma—perform. Among the stars who frequented the French Quarter Inn: Frank Sinatra, Benny Goodman, Robert Mitchum, Brenda Lee, and Robert Goulet. Comedian Jonathan Winters occasionally performed his routines there as well. Fountain's clubs became a mecca for celebrities who wore their visits to his venue as a badge of honor.

Fountain was a founding member of the “Half-Fast Walking Club,” one the most famous of New Orleans’ many marching jazz bands.

In addition to Dixieland, Fountain was also an enthusiastic promoter and performer of a variety of other jazz sounds, including honky tonk, jazz pop, and Creole.

In later life, Fountain became a staple of jazz festivals around the country, and he remained an active performer in casinos and musical shows along the Gulf Coast of Mississippi. Fountain kept a second home there, a house which was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Glenn Frey: The Passing of a Rock and Roll Legend; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; January 19, 2016.

David Bowie: The Life of an Audacious Innovator; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; January 11, 2016.