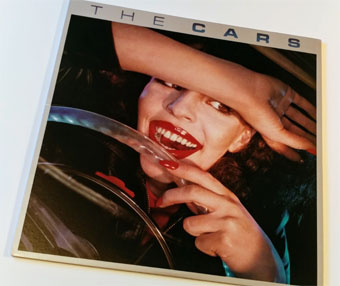

photo courtesy of Thursday Review

The Cars: A Look at Their Debut 40 Years Later

| published August 3, 2018 |

By R. Alan Clanton, Thursday Review editor

Of all the recent music anniversaries and retrospectives discussed here at Thursday Review, one deserves special attention as the album passes into its 40th year, and as the band we examine found itself entering the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame earlier this year—joining the likes of Bon Jovi and Dire Straits, and participating in tributes to the recently deceased Tom Petty.

The debut album by The Cars, released in early June of 1978, may be one of those seminal moments in music where you can recall vividly (assuming you are of a certain age and were alive in 1978, as I was) the entire cultural and social and political milieu.

Released by Elektra Records—a recording shop relatively light on music reflective of the growing anti-disco movement already reaching full strength that year—the eponymously named album entered that rarest of rock music pantheons within the first six or seven months of its existence: indeed, it quickly became an album in which literally every song received airplay on American radio. Members of the band later joked that their first album was then, and remained for years, their “greatest hits” album.

Formed in Boston in 1976, ironically at about the same time that the more famous band using the town’s name (Boston) had gained universal radio clout with its own self-titled debut album, The Cars members were part of a nebulous, often ill-defined, but increasingly potent artistic and musical rebellion against disco—an insurgency which happened to coincide happily with the parallel interest in British and American punk and the still very young New Wave movement.

And like the band Boston, The Cars had already gained huge traction in the nightclub scene in and around Bean Town, routinely packing houses and establishing a loyal following throughout the music scenes in other towns and communities in Massachusetts. And, also like Boston, the band’s skill and chemistry made it possible to convince local radio stations to give The Cars’ several demos—recorded in small studios in the Boston area—enough airplay to plant seeds in an already fertile musical soil.

Among their first gigs: a New Year’s Eve live show at a dance at Pease Air National Guard Base in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The band performed regularly at small and medium-sized venues in New England, all the while aware that at a song from their demo tape, “Just What I Needed,” was gaining exposure on several radio stations in Boston, including WCOZ, a then popular album-oriented rock and roll station whose powerful signal in those days could carry as far north as Vermont and New Hampshire and as far south as Montauk Point.

About the same time that the band was yearning for validation, they were approached by multiple labels, among them Arista—the company well known for its collaborations with numerous new wave, glam rock, punk, and progressive bands and acts (Iggy Pop, Gary Glitter, Ian Dury, Dave Edmunds, the Alan Parsons Project). But the group signed instead with Elektra, which—sensing that the label may be missing opportunities in the rapidly-expanding overlapping styles—courted the band more aggressively. For band members, it was also a strategic decision: with Elektra, The Cars would be an edgy stand-out among acts largely centered on the west coast.

The decision would prove to be a crucial plus for both the band and the label, what would prove more pivotal would be the band’s artistic sensibilities and sense of timing—a convergence whereupon the newness and freshness of the larger New Wave movement would work well within the context of a band with truly punchy, effective rock and roll hooks and lyrics. The band was in the right place—and with the right set of skills—to catch lightning in a bottle.

Though the band—like many rock and roll groups—would morph and evolve in its pre-studio days, rolling uneasily through a variety of styles (jazz, swing, blues, folk music, electronic, acoustic) none of these genres suited the band’s founding two members, Ric Ocasek and Benjamin Orr. Eventually, as if drawn by magnetic forces, the two decided to keep the sound simple and straightforward: rock and roll, with an emphasis on minimalism and punch. Previous band members drifted away or wired fired, and soon three new members joined the group: guitarist Elliot Easton, keyboardist/sax player Greg Hawkes, and percussionist David Robinson, a skilled drummer with an almost equally high degree of passion for visual art. It would be Robinson who suggested the more evocative but Spartan name for the band, The Cars.

Recorded in February of 1978 but not released until June of that same year, The Cars self-titled first album was fast out of the starting gate. Though on the Billboard Top 200 chart it peaked as an album at number 18 the following spring, the relative fair-to-middling “LP” ranking belies the album’s earth-shaking power. Between June 1978 and December 1978, The Cars had already sold more than a million copies (taking it to “Platinum” status), and it would keep selling well into the following year. It would spend a staggering 139 weeks on the Top 200 rankings, and would—for a time—actually perform even better in the U.K., Canada, Australia and New Zealand. By midway through 1979, one year after its release, The Cars had gone “Double Platinum” in Canada, and were approaching the two million units sold mark in the U.S.

Much of that strength derived from the potency of the album’s mere nine songs, any of which—indeed, all of which—one can easily still hear today on broadcast and satellite radio within any given hour. And like their multinational contemporaries The Police, the music itself would eventually transcend linkage to any musical categorization. The Cars tunes even now have easily outlived most younger listeners’ understanding of what “New Wave” even means, or meant then.

Among those nine songs were three singles released between May 1978 and March 1979: “Just What I Needed,” “My Best Friend’s Girl,” and “Good Times Roll.” In the colorful context of the New Wave movement, any one of those songs would have been enough to carry an album forward toward the top of the charts (how many copies of the debut album of The Knack were sold on the singular power of only one song, “My Sharona”?). But The Cars had three smash singles all of which moved heartily into the Top 40.

Not that the album rested on those laudable laurels. Released at the zenith of what was then called album-oriented radio, the record also had six additional songs worth note—all catchy, all zingers, all exceptionally performed and neatly engineered. And as a result every song on the album received solid airplay on FM. The record had a lot of everything that mattered in the post-disco explosion: infectious, well-crafted hard rock guitar hooks and memorable chord progressions; hard-driving but minimalist-catchy percussion, just the right amount of synthesizer and electronic bells-and-whistles (too little, and the sound would have been stripped bare; too much and the band’s identity might have ever blurred), and Ocasek’s trademark pithy lyrics—at times opaque, often endearing, seemingly so memorable that they remain fun even now, decades later. (Let them leave you up in the air/let them comb your rock and roll hair/let the good times roll.

Aside from the three official singles, the album’s other notable tunes include “You’re All I’ve Got Tonight,” (which became a de facto single, receiving almost as much airplay as the first three songs), “Bye Bye Love,” which became a staple of album-oriented radio, and “Don’t Cha Stop,” another radio favorite and a tune which has endured despite never having spent a minute on any “chart,” anywhere in the world. Then there is the album’s penultimate tune, “Moving in Stereo,” another album-oriented staple made even more durable and more infamous for its role in the classic coming-of-age movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High, a film which made stars of Judge Reinhold, Sean Penn, Forest Whitaker and Jennifer Jason Leigh, and brought new meaning to the term “fantasy sequence” when actress Phoebe Cates emerged from a backyard swimming pool.

In fact, every song on the group’s eponymously named album gained some form a radio traction, or subsequent exposure in film and TV, and the album—even now—remains a joy to listen to from start to finish as sort of package deal—rare for any album, rarer still for a recording debut. This puts The Cars in a small, elite club of rock and roll artists and bands for whom their first recording remains classical and historically enduring: Boston’s self-titled debut from 1976 (the biggest selling debut album in history at the time, with more than 1 million units sold in less than six months), The Eagles minimalist-named album (which includes the iconic “Take it Easy”), Led Zeppelin’s eponymous 1969 debut (widely considering the album which invented both heavy metal and the enduring new de facto component of rock, the guitar riff), Bruce Springsteen’s poetic Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ, and later debut albums by Third Eye Blind, The Clash, Guns N’ Roses, and The Strokes.

What’s more, the album and its nine songs—taking as a package or as individual tunes—remains appealing and fresh and infinitely infectious, even decades later. As Rolling Stone magazine said, “No band has ever knocked out a debut so packed with straight-to-car-radio classics.” The Cars was a turning point in rock music history, so add it to you list of 100 albums you must listen to (from start to finish) before you die.

Related Thursday Review articles:

Reflections on the Death of Tom Petty; R. Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; October 3, 2017.

A Splendid Time is Guaranteed for All: Sgt. Pepper at 50; Kevin Robbie and Alan Clanton; Thursday Review; June 14, 2017.